73 Years of Aficion: Valeriano Salceda, “Giraldez” Has Seen Almost Everything; And He’s Telling…

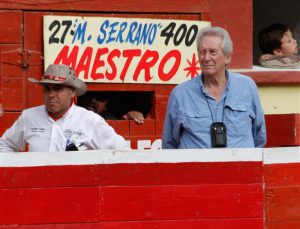

His given name is Valeriano Salceda. You could be forgiven for not knowing that—even if you knew his distinctive profile; at least a full foot taller than most of the professionals whose exploits he has documented for over 50 years, long in every aspect, arms, legs, hands, face; once black hair now whitened with 83 winters—because everyone who addresses him calls him by his real name—”Maestro”. While many honorary titles in Mexico are used in jest, this title, about this man, is clearly reverent.

Valerian Salceda, “Giraldez” to aficionados of the corrida, is 83 years young. He began the interview with a request to talk “not about me, only about the bulls, if that’s what we’re her to discuss.” A not unexpected response for a man whose passion for bulls and matadors stretches as far back as he can remember. A passion he never felt compelled to pursue, “I’m crazy, but not that crazy…” he laughs with that intimidating authority that somehow communicates the idea that, if you, too, must laugh, it should be LIKE THIS.

In 1957, he was asked by the inspirational empresario and bull breeder, Salvador Lopez-Hurtado, to broadcast the most notable corridas from Lopez-Hurtado’s Plaza Monumental de Juarez—at that time sponsored by the famous Moctezuma Brewery; and later, when Lopez-Hurtado erected his Monumental Playas de Tijuana, to be the exclusive voice for those corridas; a job Salceda took as something of a lark. He has done broadcasts of corridas from Plaza Mexico and Las Ventas in Madrid, but his home, since 1960, has been Tijuana.

Giraldez, in addition to his radio broadcasts, has been the host of many radio and television programs about los toros, authored a number of books, and edited and written for several magazines, in the days when such material more readily sold. When he speaks of bulls his authority is nearly unchallenged, and his dictums regarding the relative worth, or lack, of a particular torero, bull, ranch, breeder or plaza are taken with all the gravity of Fortune 500 CEOs pondering the pronouncements of Alan Greenspan. His anecdotes regarding the greatness—and great foibles—of the principals are legend, and when asked if one particular occurrence distills the essence of the fiesta, he replies with a memory of the great Rafael Rodriguez, known as the “Volcano of Aguascalientes” performing in a small, out of the way town in central Mexico, “already a millionaire, with a family…a recognized star,” risking his life against difficult, dangerous bulls, because “this is my path—I can’t be anything other than I what I am; if I don’t fight this bull the way I know how, I’ll lose my way…”

Giraldez does not hedge his statements; his ideas and opinions are given without hesitation and with the authority of a man who has the conviction of his beliefs. In regards to the future of the fiesta; “It’s many things; it has to be handed down, from in families, from father to son; it’s publicity, information, a reserve of understanding about the spectacle; in the press—there were 5 newspaper dailies when I was young, each with a large section on the bulls, and 6 or 7 daily radio programs where it was discussed at length. When I started, I did a half hour program every day except Sundays; now, where can you find out? It’s outreach to new audiences. There was a program here which distributed 300 free tickets to the corrida to university students; young people who didn’t have the finances at the time to attend, but who, when they got their degrees and arranged their lives, would be the public of the future; but it didn’t last. It’s the bulls; if they continue breeding out the fiereza—the fire and aggressiveness of the bulls in favor of a pretty show, who knows? But for a torero, un toro enrazado—a combative, spirited bull, is much more difficult; and there are only 5 or 6 in Mexico who can deal with them and the public doesn’t know how to see that…”

He brooks no argument for defense of the bull; “Half the population of Mexico would like to live as well as the toro de lidia; food, medical care, freedom; instead, so many work for giant companies that make millions a week and they’re paid $1,000 pesos (about $76)—and if you think about the animals farmed for food; piled up one on top of the other, no freedom, force fed—the toro bravo is privileged; I don’t worry about the bull.”

Neither does he hesitate when sharing his personal favorite, “Silverio, no one else has made me feel el toreo that way; he was both a great artist and un torero fino—a great stylist; he had his up and down moments, but no one else was like Silverio…”