Growers Move to Gut California’s Farm Labor Law

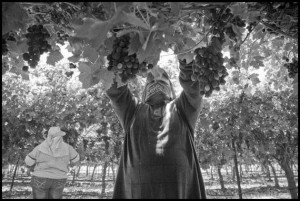

When hundreds of people marched to the Los Angeles City Council last October, urging it to pass a resolution supporting a farm worker union fight taking place in California’s San Joaquin Valley, hardly anyone had ever heard the name of the company involved. That may not be the case much longer. Gerawan Farming, one of the country’s largest growers, with 5,000 people picking its grapes and peaches, is challenging the California law that makes farm workers’ union rights enforceable. Lining up behind Gerawan are national anti-union think tanks. What began as a local struggle by one grower family to avoid a union contract is getting bigger, and the stakes are getting much higher.

When hundreds of people marched to the Los Angeles City Council last October, urging it to pass a resolution supporting a farm worker union fight taking place in California’s San Joaquin Valley, hardly anyone had ever heard the name of the company involved. That may not be the case much longer. Gerawan Farming, one of the country’s largest growers, with 5,000 people picking its grapes and peaches, is challenging the California law that makes farm workers’ union rights enforceable. Lining up behind Gerawan are national anti-union think tanks. What began as a local struggle by one grower family to avoid a union contract is getting bigger, and the stakes are getting much higher.

The Gerawan workers got the City Council’s support and, on February 10, the Los Angeles Unified School District Board of Education passed a resolution that went beyond just an encouraging statement. The LAUSD purchases Gerawan’s Prima label peaches and grapes through suppliers for 1,270 schools and 907,000 students. The LAUSD’s resolution, proposed by board member Steve Zimmer, requires the district to verify that Gerawan Farming is abiding by state labor laws, “and to immediately implement the agreement issued by the neutral mediator and the state of California.”

Verifying compliance, however, may not be easy. In mid-March a hearing on Gerawan’s violations of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA) ended after 104 days of testimony by 130 witnesses. According to the Agricultural Labor Relations’ Board’s general counsel, Sylvia Torres-Guillén, and its regional director in Visalia, Silas Shawver, Gera-wan mounted an intense campaign against the United Farm Workers after the union requested bargaining in October 2012. According to the board, Gerawan sought to “undermine the UFW’s status as its employees’ bargaining representative; to turn its employees against the union; to promote decertification of the UFW; and to prevent the UFW from ever representing its employees under a collective bargaining agreement.”

The conflict at Gerawan Farming has been building for 26 years. In 1990 over a thousand workers voted in a union election in its fields near Madera, in the San Joaquin Valley, choosing the United Farm Workers.

Five years after that election, having exhausted legal efforts to overturn it, Mike Gerawan finally sat down with UFW representatives. Instead of negotiating, however, he told them: “I don’t want the union and I don’t need the union.” That ended bargaining before it even started. Over the next 17 years, with no contract, Gerawan Farming grew to become one of the nation’s largest growers, exporting its Prima label fruit globally.

Hardball tactics towards unions in the fields have been typical of California growers. Although the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975 gave farm workers the right to vote for unions, the law had no teeth to force unwilling growers to negotiate contracts afterwards. According to UC Davis professor Philip Martin, workers were unable to win agreements in 243 of 428 farms where they’d voted for the UFW between 1975 and 2002.

Federal law has never covered farm workers. Outside of California, no state has a law giving farm workers a legal process for recognition and bargaining. The few union agreements that exist in other states are the products of long campaigns and boycotts. As a result, less than one percent of the nation’s farm workers have union contracts.

In 2002, however, California’s legislature passed two bills that amended the original law. Today the ALRA allows a union to ask for a mediator if a grower won’t reach agreement on a first-time contract. Once the Board adopts the mediator’s report it becomes a contract. The process is called mandatory mediation. Growers challenged this process and lost at the state court of appeals in 2006. The UFW has since used the law to negotiate contracts at several large employers, covering about 3000 workers.

In 2012 the UFW made another demand for bargaining at Gerawan. This time, according to the labor board, the company unleashed a sophisticated drive, not just against the union but against the law itself. In that effort, it’s acquired the help of some of the country’s most conservative advocacy groups and think tanks. Losing mandatory mediation would be devastating to the UFW. No real union can survive indefinitely without being able to win contracts, and through them, gain members and improve wages and conditions.

A Dirty Election

The UFW says it continued working with Gerawan workers to improve conditions during the 17-year hiatus between 1995 and 2012.

[T]he UFW renewed its bargaining demand in October 2012, and union workers chose a negotiating committee. This time the company sat down at the bargaining table – from January to July of 2013. But when bargaining went nowhere, the union filed for mandatory mediation.

A key allegation in the ALRB complaint charges Gerawan Farming with manipulating wages to keep the union out. The company boasts it pays $11.00/hour — $2 above the state minimum — and says it shows workers are better off without a union. Fifteen-year employee Severino Salas believes, however, “it’s the pressure from the union” that got the company to raise wages. “They’re not giving us $11 for nothing,” adds Rodriguez. “Until recently they’d accuse whole crews of not working fast enough and fire them.”

In June 2013, while bargaining was going on, Gerawan rehired Silvia Lopez, a previous employee whose boyfriend was a company supervisor, and whose daughter and son-in-law also work there. Lopez “began her involvement in anti-union activities at Gerawan before she started working for the company,” according to the ALRB. Almost immediately she became a client of Paul Bauer, a lawyer for a Fresno firm representing employers in labor disputes.

Lopez began to collect signatures on a petition for a decertification election to get rid of the UFW.

In August 2013 Dan Gerawan invited Lopez and her friends to go with him to Sacramento, to testify against a bill that would have strengthened mandatory mediation. On September 18, as the mediator prepared to issue his report, Lopez turned in her petitions. Shawver and his staff compared the signatures to the employee list and found there weren’t enough.

By then, Sylvia Lopez had an additional lawyer, Anthony Raimondo, who also represents Gerawan’s two largest labor contractors, Sunshine Agricultural Services and R&T Grafting Labor. He asked for more time, and signature collection went into overdrive. Of the additional signatures he turned in, an exhaustive investigation found at least 100 were forged, allegedly from workers employed by Raimondo’s contractor clients. The decertification petition was dismissed.

A second decertification campaign was immediately launched. On September 27 the company gave time off to hundreds of workers, to leave their crews and go to Visalia to demonstrate outside the ALRB office. According to the ALRB, the following Monday supervisors shut down work entirely, blocked entry to the fields and packing sheds, handed out petitions and demanded that workers sign. A statement by Gera-wan claims “1500 workers walked out of the fields,” and describes this as “the largest ever seen in California’s agricultural industry.”

Two days later the California Grape and Tree Fruit League, a grower organization, supplied busses, food and anti-union tee-shirts to Gerawan workers, taking them to Sacramento to lobby for decertification.

Meanwhile a media campaign produced TV and newspaper stories alleging workers were being denied the right to vote in a decertification election. The labor board in Sacramento, whose appointed members have final say over the agency’s decisions, seesawed back and forth.

First it delayed approving the contract drawn up by the mediator.

But then Shawver and Torres-Guillén rejected the second petition as well. When the company appealed, the labor board ordered them to conduct the decertification election anyway, despite the charges of company interference.

Workers voted on November 5, 2013. Their votes were impounded, however. Legally, they cannot be counted unless an investigation concludes the company had nothing to do with organizing the decertification campaign.

After the election, the ALRB finally approved the mediator’s contract. Gerawan Farming refused to implement it, and Torres-Guillen formally charged the company with violating the mandatory mediation law.

Gerawan then asked a judge at the state court of appeals in Fresno to declare mandatory mediation unconstitutional, overturning the 2006 decision upholding it. Joining Gerawan were the Western Growers Association, the California Farm Bureau Federation and the California Grape and Tree Fruit League (now the California Fresh Fruit Association). Even Lopez and Raimondo filed an amicus brief.

A Gerawan statement claims, “We support [workers’] right to choose, but the ALRB staff and the UFW do not. Our sole message to our employees has never wavered: ‘We want what you want.’ There is now only one correct and just solution to ensure employees’ rights are protected. Count the ballots.”

According to veteran labor lawyer David Rosenfeld, who teaches law at the University of California’s Boalt Hall Law School, “Gerawan has all the money in the world, and doesn’t lose anything by appealing. In the meantime, they can delay implementing the contract for at least a couple of years.” The company’s problem, he believes, is that the state supreme court is generally favorable to workers’ issues.

Conservative Groups Gather Around Gerawan

As this fight unfolds national anti-union organizations are moving in. The Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence joined the appeals case. This far-right legal institute holds that “The right to acquire, protect, and enjoy property was considered to be one of the fundamental, inalienable natural rights of mankind.” In recent years the Center has joined the Harris v. Quinn suit against the Service Employees International Union in Illinois, sued the California Labor Commissioner on behalf of employers, argued for Hobby Lobby Stores against birth control, and supported the initiative to end affirmative action in Michigan.

Much of the San Joaquin Valley is conservative Republican territory. In “The Perfect Fruit,” author Chip Brantley quotes Ray Gerawan: “My philosophy is survival of the fittest,” he says. “In this family, we’re real big on free enterprise.” He says his ambition is “to put my competitors out of business … because that makes us all stronger.”

This year the Gerawan’s local state assembly member, Republican Jim Patterson of Fresno, introduced AB 1389. It would allow groups like Sylvia Lopez and her friends to inject themselves into mandatory mediation proceedings on the same basis as the union’s elected negotiating committee. Further, it would allow growers to decertify unions that “abandon” workers for three years, an obvious reference to Gerawan. Both measures would make mandatory mediation essentially unworkable.

[C]ity councils in New York City and Washington D.C. are taking up measures like Los Angeles’. The grower’s biggest buyer is Wal-Mart, an inviting target for people already angry at that chain’s treatment of its own workers. After the LA City Council vote, Maria Elena Durazo, at the time still the head of the county labor federation, warned Gerawan Farming of a possible boycott: “You will not be welcome in the stores of Los Angeles if that’s the next thing these workers ask us to do.”

The Impact of Decertification

Decertification is more than just the key to undoing the original election that required Gerawan to bargain. If holding an election can’t actually lead to a contract, there’s not much reason for workers anywhere to risk their jobs supporting a union. Growers far beyond Gerawan, therefore, have an interest in the outcome – the reason why the Grape and Tree Fruit League and national conservative groups are paying attention.

A stronger union in California fields could raise wages (and growers’ labor costs), which are far lower now than they were thirty years ago when the UFW was at its strongest. One recent study found that tens of thousands of Mexican indigenous farm workers in California receive less than minimum wage.

[E]nforcement of the mediator’s contract at Gerawan seems far away to the company’s workers. While the grower continues to operate without it, UFW supporters like Salas say they face retaliation. “I’ve worked for Gerawan since 1999,” he told Capital and Main. “The foreman realized I was for the union when they began passing around the petition and I wouldn’t sign it.” He was denied work along with his wife in their normal crew. “What the company really wants is for us to quit,” he charges.

This is an edited version of the story that was originally published in Capital and Main, http://capitalandmain.com/latest-news/issues/labor-and-economy/growers-move-gut-californias-farm-labor-law/