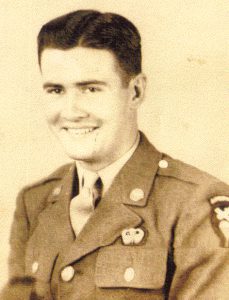

Louis Flores a Screaming Eagle

Sixty-six years ago my uncle, Louis B. Flores, was a paratrooper serving with Easy Company (alternately with HQ Company) in the 101st Airborne Division during the D-Day invasion at Normandy—later at the Battle of the Bulge and he had more than 50 jumps in combat conditions. He was with the same group depicted in the Hollywood version “Saving Private Ryan” starring Tom Hanks.

His former commanding officer was Lt. Dick Winters, an inspiration for the Stephen Spielberg hit HBO series “Band of Brothers.” Winters died a few days ago, and the news of his death was just widely released.

And a few years ago, he spoke about my uncle during an interview. They were together in some of the most intense fighting of the war. My uncle was a sergeant under him.

My uncle died from cancer at age 77 nine years ago, but the war was always with him and he often attended 101st Airborne reunions over the years.

All his life, he’d been a rough-and-tumble daredevil, legendary at an early age for his luck and composure in dire straits. He was unlike the other children in his family of seven—four boys and three girls—all born and reared in the hills of North Louisiana during the Great Depression. Hard times, certainly.

He was among hundreds of thousands of young Americans during that time called upon to defend America at a moment of maximum danger. He enlisted in the Army at age 19, in 1944, and volunteered for the paratroopers for the extra pay and because he wanted to be the best, he once told me.

At an early age he had the reputation of wanting to do things his way, at the risk of a whipping. Like the time, at about age nine or 10, when he decided he did not want the family housekeeper to give him a bath. So he grabbed a .22-caliber rifle and ran the woman out of the house.

The surviving three kids still laugh about that when they get together.

I first became aware of my uncle’s exploits in World War II as a young boy. My father, his younger brother by several years, was always in awe of him especially after he returned from the war with only a few shrapnel wounds to show for his trouble.

One of the highlights of my childhood was when my uncle took my brother and I out to a sand pit near his home in the bayou country of Grand Coteau, Louisiana. He brought along his 9 mm P-38, a German officer’s pistol taken from a dead Nazi in the field. It was in the original leather holster. He opened it and handed the pistol to me after careful instructions. I aimed at a nearby empty can, and fired. To me it was like a battleship’s gun, recoiling amid smoke and thunder and glory. At that moment I felt like a member of an elite group.

That was many years ago but it seems like only a short time back. He worked many years after the war as a welder, mostly for Exxon, and later on his own as a contractor. But to my brother and I, he was a star. And thank God for him, and his old commanding officer, Dick Winters, and so many other young men like them who were not afraid to rumble with the vaunted “Supermen” of the Third Reich—the Hitler-dazed Nazis bent on dominating much of the world.

At the Battle of the Bulge, my uncle’s unit of “Screaming Eagles” were totally surrounded by the Germans at Bastogne. Uncle Louis rarely talked about the war, but he told me a few things over the years. Like the times he had to cover himself, in the terrible cold, with the bodies of dead American soldiers, in foxholes, as German troops raked the area with random shots and bayonets—to make sure everyone was dead. He told about the long, freezing hours confined to a foxhole or trench, under enemy fire, unable to move even for a bowel movement or to urinate. So they all had to just do it in their fatigues.

“One time me and another man were on a recon mission with a bazooka, and we happened upon a German Panzer tank. I held the bazooka, and my buddy loaded it, I aimed and fired, but the shell just bounced off that tank’s armor like it was from a pellet gun. So we just looked at each other as the tank’s turret started around toward us, and we headed for the hills,” he said.

Finally, those paratroopers were rescued by unexpected sunny weather, allowing much needed supplies to be parachuted from cargo planes. And General George Patton rolled in about the same time with his division of tanks. And Patton with the paratroopers turned the tables on the Germans, rapidly.

Later, the role of the 101st seemed endless as they prepared—after Germany surrendered—for a jump into mainland Japan. But the atomic bombs were dropped in August 1945 and Japan finally gave up too.

The film “Saving Private Ryan” was, by all expert accounts—including Dick Winters—a highly accurate portrayal of the horrendous brutality of their war experience. After I saw the film, it hit me that no wonder he never spoke much about the war.

My brother and I practically idolized our uncle, and we thought of him as invulnerable—the original iron man. A true survivor of the worst combat imaginable. Even though he died, it did not diminish at all the way he always thought of him.

As long as America has people like him around there will always be hope for the freedom that America fights to achieve for our country, and for others.

God bless Dick Winters, my uncle, and the Screaming Eagles of the 101st Airborne, of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.