SD City Attorney Used Cash to Pay Legal Fees to Rival, Misdirected One Payment

San Diego City Attorney Mara Elliott used cash to pay thousands of dollars in legal fees she owed her recent campaign opponent, according to receipts she signed to confirm the payments.

Elliott paid $3,255.77 in cash as part of over $8,000 in legal fees she owed local attorney Cory Briggs after he won two lawsuits filed between the political rivals.

The first case was a lawsuit filed by Elliott to challenge Briggs’ use of the term “Taxpayer Advocate” as his ballot designation during last year’s election. The judge in that case ruled that Briggs’ history of challenging tax increases and government waste allowed him to use the term to describe himself to voters.

Elliott was ordered to reimburse Briggs over $7,000 in legal fees and costs.

In the second case, Briggs sued to challenge Elliott’s use of a San Diego Union-Tribune (SDUT) endorsement during last year’s General Election. Briggs argued that Elliott was misleading voters by using the SDUT endorsement which she had received for the Primary Election on her ballot statement for the General Election even though the newspaper had not yet made any endorsements for the runoff.

The judge agreed with Briggs and ordered the Registrar of Voters to remove Elliott’s reference to the newspaper endorsement from the General Election ballots before they were printed, and ordered Elliott to reimburse Briggs $950 dollars in costs, plus interest. Briggs had represented himself in that case.

The SDUT later endorsed Elliott for the General Election and she eventually won the November 2020 election.

Elliott paid a little over $5,000 toward the judgment in the ballot designation case in May of this year, but still owed additional fees, costs, and interests.

On Tuesday, Briggs and Elliott appeared in the downtown courtroom on the ballot designation case for what is known as an ORAP, or Order for Appearance and Examination of the Judgment Debtor, which is used by the court to question debtors as to their ability to satisfy a judgment.

Briggs and Elliott appeared on their own behalfs without other lawyers.

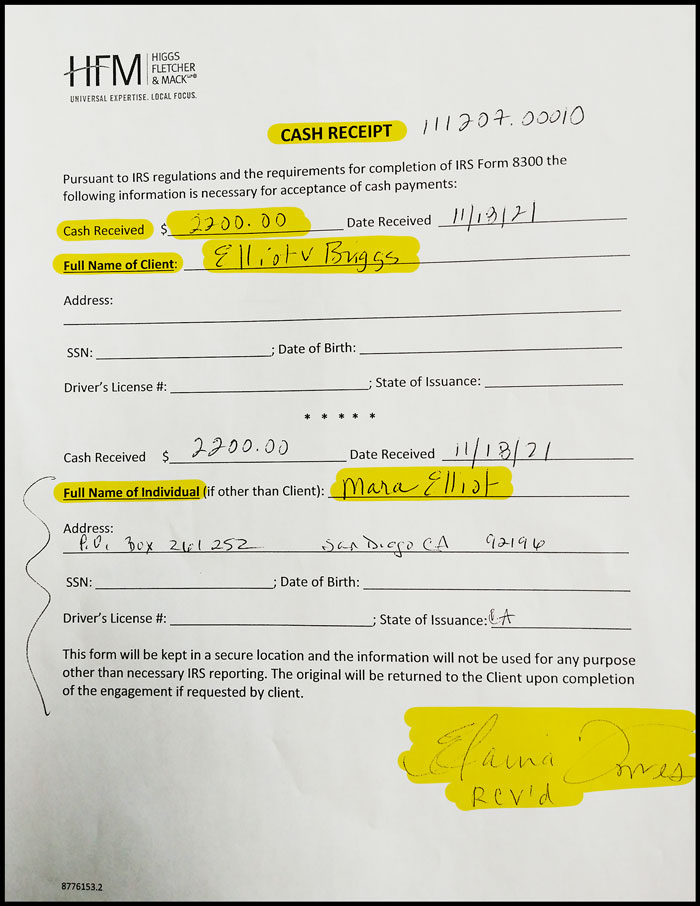

Elliott had earlier filed a brief with the court outlining that she had recently made a cash payment of $2,200 to the law firm of Higgs, Fletcher & Mack which had represented Briggs in the ballot designation case. Briggs had not been notified of any payments having been made toward his fees.

During the hearing, Briggs offered Elliott to reschedule the hearing in a month or two to allow them to agree on the final outstanding fees, but Elliott insisted that the judge make a final ruling on the spot.

The judge instead cancelled the ORAP hearing for the day. The court did not make any decision and allowed Briggs time to calculate his final fees, costs, and interest to be submitted in a subsequent motion in the near future.

After the two rivals left the courtroom, Elliott decided to share an elevator with Briggs as the two left the building without incident.

Later the same day, however, Elliott emailed Briggs a receipt which she received from Higgs Fletcher when she dropped off $2,200 in cash in an attempt to make a payment toward the judgement in the ballot designation case. The receipt was signed by a Higgs employee as having received the cash payment on November 18th.

But, the receipt showed Elliott wrote in the name of the client as “Elliott V Briggs” instead of Cory Briggs. The ballot designation case handled by the law firm is named Elliott v. Maland because Elliott actually sued San Diego City Clerk Elizabeth Marland and Michael Vu, the San Diego County Registrar of Voters, to challenge Briggs’ ballot designation, not Briggs himself.

The following day, Briggs received an emailed letter from Elliott where she complained that he had sent a private process server to her home weeks earlier to deliver the ORAP hearing notice even though she is “at risk” due to the work she does because “work on gun violence prevention has garnered national attention, and not everyone is happy about it.“

Elliott also complained to Briggs that “you repeatedly use my home address on court pleadings even though I use a PO Box for litigation” and that she has “filed the appropriate papers to keep my home address confidential, yet you seem intent on publicizing my home address, placing me and my family at risk.”

The email also warned Briggs that that if he is “unable to respect boundaries, and insist on sending agents to my home, I will seek protection from the court” and ended the letter by writing that his “conduct has gone on for far too long, and your obsession with me is concerning.”

But, Elliott did not raise any of these issues with the judge the previous day, nor did she mention her concerns to Briggs before, during, or after the court hearing, or when they rode the elevator together.

Briggs responded to her letter by email on Wednesday, explaining that he used her home address to serve her as per state law which requires service at “the attorney’s residence” if they do not have an office address. Elliott is representing herself in her personal capacity in the two cases because they are not connected to her official work as City Attorney, and she does not have a private practice office, so Briggs was required to serve her at her home.

Briggs also pointed out that he had “previously tried to have you personally served at your public office, but your receptionists always refuse to contact you to come out to receive personal service and they refuse to sign for anything on your behalf as a party to non-municipal litigation.”

The email also clarified that Elliott’s home address is not confidential and is easily found on the Internet. Briggs included four search results that show Elliott’s home address, contact information, and even her husband’s name at the same address.

“After reading your letter, I did a quick online search for you and several websites providing your name, your home address, your age, and in some cases your husband’s name immediately popped up; see attached. That’s why any suggestion that I am promoting your whereabouts is absurd,” Briggs wrote.

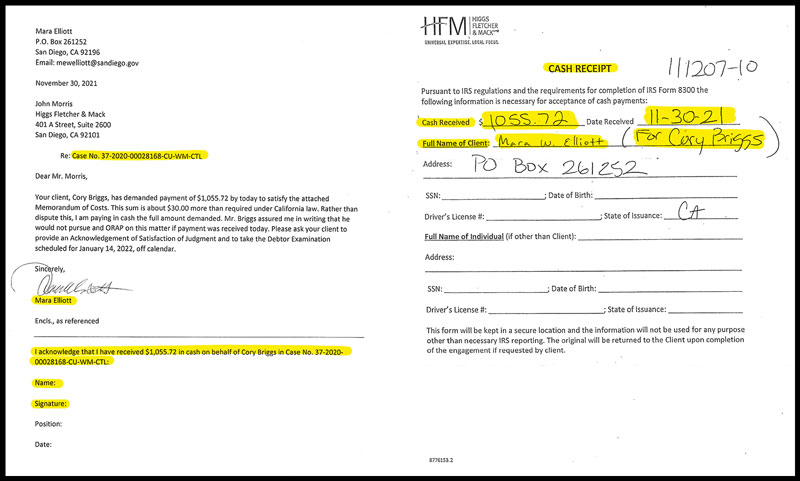

On Thursday, Briggs received another email from Elliott indicating that she had “dropped off the payment you demanded on the UT case at [Higgs Fletcher & Mack] on 11/30“, and attached both a letter she wrote to the law firm indicating the payment was for the UT case, as well as a receipt on the firm’s letterhead for the cash.

Although the two documents are dated on the same date as the Tuesday hearing, neither of the documents have any signature from anyone at the law firm confirming receipt of the cash, and the case number Elliott listed is the SDUT endorsement case which the law firm did not handle. The firm only handed the ballot designation case.

Briggs responded to Elliott’s email about two and half hours later to clarify that he had previously informed both her and her attorney that the law firm of Higgs Fletcher did not represent him in the SDUT case, and that he had “informed you in writing on November 23 and Mr. Alvarez on November 29 with respect to the amount owed by you in that lawsuit, ‘[t]he check should be payable to me and delivered to my Upland office’.”

Briggs closed his email with another clarification as to when and where Elliott should send payments for the SDUT case.

“So let me be clear one more time: The amount you owe to me under the UT-endorsement judgment is to be delivered to me (either as cash, cashier’s check, or money order) at my Upland office. If you’d like to send payment by overnight courier, that’d be fine with me. But if I do not receive the payment by noon tomorrow (my office is closing early for our holiday party), I will proceed with the ORAP.”

As of Friday morning, Briggs had not yet received any payment from Elliott toward the judgment in the newspaper endorsement case.

Elliott and Briggs were also involved in another case related to last year’s campaigns.

Briggs sued Elliott for defamation claiming her campaign used misleading quotes about Briggs from a previous case but which had been amended by in a later ruling. Briggs sought $1 million in damages, but the case was thrown out when a judge ruled Elliott’s use of the language was protected speech, even if it was misleading.

The judge ordered Briggs to reimburse Elliott $29,700 in legal fees and costs. Briggs recently paid Elliott $31,450.09 for the total of her fees, costs, and interest.

Briggs has represented La Prensa San Diego in several cases related to enforcement of the California Public Records Act and Brown Act. Briggs continues to represent LPSD in pending cases filed against the City of Chula Vista, the County of San Diego, and the City of San Diego.

Alberto Garcia

Alberto Garcia