“Whenever I Got Out of School, it Was Straight to the Fields”

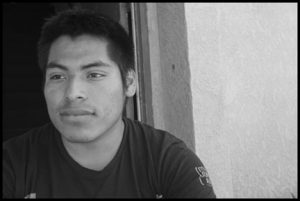

The Story of Javier Mondar-Flores Lopez

New America Media

Thanks to Farmworker Justice for its support in documenting this story.

SANTA MARIA, CA — Growing up in a farmworking family — well, it’s everything I ever knew. Whenever I got out of school, it was straight to the fields to get a little bit of money and help the family out. That’s pretty much the only job I ever knew. In general we would work on the weekends and in the summers. When I was younger it would be right after school, and then during vacations.

My sister Teresa slept in the living room and one night when I was doing my homework at the table, I could hear her crying because she had so much pain in her hands. My mother and my other sister complained about how much their backs hurt. My brother talked about his back pain as well. It’s pretty sad. I always hear my family talk about how much they’re in pain and how’s it’s impossible for me to help them.

I always moved. In my high school years, I moved six times. In junior high I moved three times and in elementary school I’m not sure. I went to six different elementary schools. For a while we went to Washington to work, but aside from that it’s always been in Santa Maria. We’d move because the lease ended and we couldn’t afford the rent, so we tried to look for a cheaper place.

We always lived with other families. The first time I can remember we lived with four other families. The second house we lived with five families. Each family gets their own room and does their own cooking. They get their own space in the kitchen cabinets and the refrigerator. When they cook in the morning before work it gets pretty chaotic in there.

It’s hard sharing the bathroom with so many people in the house. They try to kid around about it. I remember I was always a morning student, so I would wake up and take a shower. My older siblings would tell me to get out because I already had a huge line waiting for me to finish. It was always in and out, flush after flush. In the morning people are rushing to work so they try and make the best out of it. Plus you can’t be late or you lose your job.

The first time I worked in the fields was when I was seven, in Washington, where I picked cucumbers. It was summer. We didn’t go to school in Washington [but] the foremen never said anything because my brother knew them. He worked in the crew, so the foremen were OK with it. There were other kids there as well. It wasn’t a huge company, just a small rancher.

When they paid by the hour we couldn’t work. If [workers] were paid by the hour and they were slow, the foreman would send them home and not let them work anymore. They would only let kids work if they were doing piece rate. We were actually really slow because we were only in third or fourth grade.

The first [paycheck I received] was for $40. I was crying because I counted my boxes that day and I knew how much I had earned that week. When the foreman gave me my pay he said I hadn’t worked [more than that]. I was in fourth grade.

I was crying because I had worked and really wanted my money. I wanted to buy something with it. Finally he paid me my money in a white envelope. I was pretty happy.

When we got older, we did get more money. We got to earn our own money because before then my mother would take everything we earned. As we got older we had more interest in money, so we would keep half of it. We were getting our own pay, and my older siblings would ask us to give half.

The biggest problem was working in the vineyards. I worked for three months in the summer and it was the hardest work I’ve ever done. They gave us clippers to clip the vines, and that’s what you did all day. Clip them and pull the grapes off.

When I got home my hands hurt so much I couldn’t make a fist or hold a cup or anything. I would just lie down since the pain just stayed. In the morning there was nothing else I could do, just go out there and work again.

In the weekends in elementary school it was pretty easy working on the weekends and going to school during the week.

They didn’t give us much work and school came pretty easy. I would like to think that I am a good student. I took predominately AP and Honors classes, and got good grades — mostly A’s and B’s. I never got any C’s.

I felt discrimination, not so much because I’m from an immigrant family, but because I’m indigenous [Mixtec]. The first time I was in second grade, kids would call us “Oaxaca.” Apparently that’s a bad thing… they would think of us as beneath them. Even in the fields. For example, one foreman divided the Oax-aqueños and the Mexicans. He put the Oaxaqueños in the bad fields and the Mexicans in the fields with no weeds.

Everywhere we went — the welfare office, the hospital — we were always discriminated against for being indigenous. Spanish-speaking and English-speaking [people] would get more information, because they couldn’t communicate with us [Mixtec speakers].

It would make the situation better for the indigenous in Santa Maria if [some of us] were working in the system.

That’s what I always wanted — to have people that actually speak our language working in the hospitals and in the welfare office, teachers in the school and in the system. Wherever we go, there would be one of us there.

In addition, I wish there were free medical care, and we were able to get overtime. You only start to get overtime after ten hours. I was pretty upset when I heard that.

When I worked in the tomatoes recently, [some workers] stole four boxes from me. I told my family to report it to the Labor Department, [but] to them it’s inevitable. They think we should just put up with it and be grateful that we have a job. [They] also fear losing their job if they make a complaint. That’s pretty much how it is. They would make fun of my dad because he would complain a lot. They’d say, “That’s why your dad is like that and never gets jobs.”

I was emancipated for about seven to eight months. My family was very conservative and strong in their Christian beliefs. I couldn’t do anything, and felt like I was trapped. I really wanted to go with my friends to dances. Plus I’m bisexual — to them that’s a sin and you’re going to hell. I couldn’t live like that. I left home and went to live with my dad. He wasn’t like I expected. He blamed me too, so I was homeless for three months.

I was working the graveyard shift, ten hours a night at C & D Zodiac, where they make jets. During the day I went to school. My AP History teacher saw I was dozing off and sleeping in class. I came out to him, and he told me, “You can’t live like this. You need to confront them.” So I went back to my family and confronted them. I became an activist, and I’ve been one ever since.

But I think it’s possible to change things, which I get from my heroes and earlier activists, like Gandhi and Martin Luther King. I’m going to go to Los Angeles and work for an organization that serves the indigenous community and then start school. I want to see how you run an organization like that, and open one here. I’ll work in the fields if I have to in order to pay off my debt, but I don’t want to work there just to earn a living.

I’m proud of what my mom and older siblings did in order to get the family here and survive. That was my motivation for choosing only AP classes. My sister didn’t get an education. None of my older sisters could go to school. I really want fairness and equality in schools. I want the discrimination against indigenous kids to stop in elementary schools. That’s where it starts. They affiliate themselves with gangs, to get it to stop. That’s the only reason.

I didn’t want to learn Spanish, because I didn’t want to lose my Mixteco language. I try to keep in touch with my indigenous roots. Whenever I cut my hair I always bury it. I asked my mother why we did that, and she says it’s because you fertilize the earth.

When it rains, I get a bowl and fill it with rainwater and drink it. I would talk with her as our bowls filled up. When I visit my dad I ask him to tell me folktales. When I have a dream I ask him to tell me what it means. I want to write down my language before it gets lost.