Battle of the Bike Lanes Pits Businesses & Residents Against City’s Climate Goals

[ESPAÑOL]

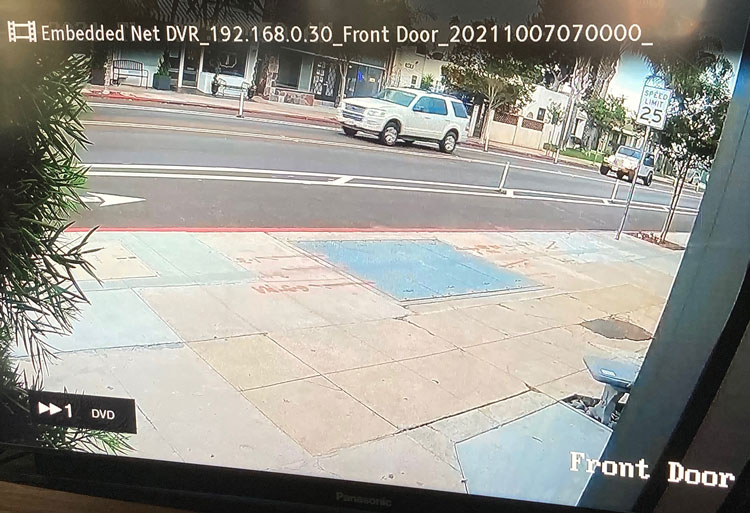

The recorded security video showed bicycles and vehicles moving past the South Park store during the morning and evening rush hours. The goal was to provide verifiable usage of the controversial 30th Street bike lanes.

The installation of the lanes was the subject of a lawsuit, which was dismissed. The fight, though, has not ended. The attorney representing the local residents and merchants has recently filed an appeal related to the 30th Street Protected Bikeways Mobility Project, the first phase of which was completed in July.

For the first time, citizens whose lives have been affected by the dual lanes have real-world data on how much bicycle traffic is moving along the new bike corridor as it intersects with Upas Street and which will eventually terminate at Adams Avenue.

The researcher, Kate Callen, a longtime North Park activist, carefully notes the numbers, often rewinding the video to recount the bicycles moving through.

“People have been asking for years for any data, the city has been saying we will get to it eventually,” said Callen, a former San Diego Bureau chief for United Press International.

A count was taken from the security video of bike lane riders (bikes, scooters, skateboards) on the 3400 block of 30th Street during peak commuting times, between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. and from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. Monday, Oct. 4 through Friday, Oct. 8. Over the course of those 20 hours, the average number of riders per peak commuting hour was 16.

Callen doesn’t live anywhere near the bike lanes but likes shopping locally. Like others interviewed for this story, she thinks the city ignored the concerns of those most affected.

Her motivation for gathering the real-time data is simple, she says: “The community was kept in the dark until just before (former Mayor Kevin) Faulconer announced it as a done deal. When people first heard about it, they didn’t believe it. How could the city do something so outrageous without telling us?”

It was in May of 2019 when Faulconer put the project in motion. Dave Rolland, the Senior Advisor of Communications for current Mayor Todd Gloria, counters that the unhappy residents and merchants did have a chance to express their opinion.

“It was an exhaustive, lengthy public planning process,” Rolland wrote in an emailed statement. He added, “When this bikeway is connected to a fully realized network of protected bike lanes, it will be widely regarded as a resounding success.”

Emails and phone calls seeking comment from the representatives of two bike advocacy organizations – Circulate San Diego and the San Diego County Bike Coalition – were not answered.

Those opposing the project say they were “blown off,” which prompted a lawsuit in 2019 to stop the project. It lost in court, says resident Pat Sexton, who created the group “Save 30th Street Parking,” claiming the group did not get a fair shake in court.

The group’s attorney, Craig Sherman, has recently filed an appeal because “we object and dispute all of the trial court’s rulings and findings.” The group had argued previously that the city never said it was removing parking places from North Park. Nor did the city provide required proof of state clearance for the major change on 30th Street, the opponents argue. In the five months since the bike corridor has been in place, the activists say their fears have proven to be true. It’s not as promised, they contend. In fact, they say, it’s been detrimental to those who work or live along the corridor.

Merchants and restaurant owners say they are seeing less business, and residents complain about being unable to find places to park.

The residents who have protested the bike lane initiative from the beginning say the city’s transportation department ramrodded the project through. They assert that the manager of its “Mobility Program,” Everette Hauser, had no interest in hearing their concerns and that he appeared to be a bike lane advocate focused on pushing through the project.

Hauser is listed on the San Diego County Bicycle coalition website as the No. 1 rider, having taken 1,191 bike trips, covering 20,678 miles through this month. Times of San Diego contacted his supervisor in order to speak to him about his job description. She responded by saying we have to file an open records act for this information.

Merchants and residents along the bike path say they appreciate the research Callen has done because they’ve wanted some solid information to bolster their contention that the limited bicycle traffic does not justify the hardship locals face every day dealing with the city-installed bike lanes. They also question the environmental value when car and truck drivers circle the area looking for parking spots or go into nearby neighborhoods to park.

The estimated total number of parking spaces lost along the entire stretch of the corridor, once it’s completed, is 450. The city has said 103 parking spaces marked by striping on the road will remain, and that another 70 spots have been added through painting angled spaces on nearby streets.

Rolland says the mayor’s office does not see the parking loss as an issue, noting that “it expands options for San Diegans of all ages and abilities to get around safely without a car and helps us achieve our ambitious climate action goals.”

Local residents living in nearby neighborhoods aren’t too happy about how this has affected their daily lives.

One woman who lives on Kalmia Street in Burlingame says her neighbors are complaining about the “extra cars on the first block of Kalmia off 30th and the added cars on Laurel and San Marcos.” While she used to go to the nearby restaurants, the woman, who asked that her name not be used, doesn’t dine out in the area anymore.

“We don’t go to the restaurants along 30th because there is no place to park in the evening,” she said.

The 30th Street corridor is still a work in progress.

Right now it runs from Juniper Street to Polk Avenue – a 1.5-mile stretch — and will eventually extend to Adams Avenue for a total of 2.4 miles.

A recent posting about the bike lanes on Next Door by a business owner near Adams and 30th says the work has begun on this last section and hopes “this will not negatively impact us.”

In a mixed-use neighborhood like North Park, it’s not just the businesses affected, it’s also the residents along the bike lanes.

Take the example of one young professional, who asked that her name not be used. Before the bike lanes were created, getting to and from her car was a breeze, she said. Not so now.

She says she has to park four blocks away and has encountered some scary confrontations, like men using foul language, as well as men grabbing their testicles and performing graphic sexual motions as she walks down 30th Street at night.

She said, “I’m a lawyer. So I get to work really long hours. And I’m often home around 6 or 7 p.m. And I have suffered from, you know, people who have done unfortunate things to scare me.” She used to carry pepper spray with her when she lived in San Francisco.

“I didn’t think I had to do this in this nice area of San Diego,” she said. But she feels very vulnerable now and chooses not to stay out late anymore.

The “under-utilized” city parking structure near University and 30th, which has been offered up as a solution for the loss of street parking, is just not working for her and many others, they say. This reporter has used the garage and has seen people sleeping in and around it. It also smells of urine in some sections of the structure.

“Just as bad, says the young lawyer, are interactions with cyclists who use abusive language and an angry tone berating her for parking in the bike lane, even if it’s only to run into her home for a few minutes.

“I am a small, you know, a young woman who lives alone, and I have to bring groceries in,” she said. “And with these bike lanes, I’m not able to even stop there and put my hazards on without being harassed.”

Her father is a longtime cyclist, she said.

“I get cycling, I get why it’s good for the environment,” she said, but does the bike lanes’ value to the environment outweigh the cost to the people along the street, she wonders

Callen says, “We have a lot of people in Save 30th Street that are avid bicyclists and have been for years.” Even with the new bicycle lanes, “they will not ride on 30th Street,” she said, because it’s too narrow and they already ride on Utah Street, which is very wide.” She added, “Nobody has really told us why the bike lanes were needed.”

Resident Brian Buckshaw, who lives on 30th and is a carpenter by trade, says, “Sometimes I’m just flabbergasted” about what he calls the “head-scratching” decision to build the bike lane when another already existed two blocks west of the 30th street corridor on Utah.

He wonders why the city didn’t use Utah, if the intent of the bike lanes was to make biking safer. The street had already been identified in the city’s bicycle master plan as a bike corridor when the bike lanes were built on 30th.

In Buckshaw’s case, he has to park away from his house now and has “a ton of tools.” He has to lug all of his boxes of saws, drills, table saws and chop saws from his car to his house. It is a particularly wearing effort to carry any plywood or lumber, and he doesn’t want to be a target for thieves. What was once a 10-minute job now takes over an hour, he says.

The residents who see him carrying the gear also give him a hard time about parking in their neighborhood, he added. Initially, Brian did try to unload quickly while parking on 30th but was berated by bicycle riders. He loves the neighborhood but is thinking about moving. “I’m getting tired of being yelled at,” he said.

For jewelry store owner Elizabeth Sapa, the pandemic was tough but the bike lanes have made it worse.

“The foot traffic that used to exist here with people walking has been eliminated,” she says. “I used to be open six days a week and I would stay open until eight o’clock on Fridays and Saturdays, because nobody’s walking around like they used to waiting for the restaurant reservations or having a good time. People aren’t doing it anymore.” She says the word has gotten out how difficult it is to park now that the city removed hundreds of parking spots.

Rod Legg, executive director at Auntie Helen’s thrift, which has been on 30th for 34 years years, is experiencing similar problems. The charity provides two bags of groceries each to 1,600 families every week, but he has noticed that seniors walking into the facility are no longer coming.

“We have noticed a decrease in our older clients,” says Legg. In addition, their laundry for people with HIV/AIDS no longer has clients coming in to use the service, Legg laments.

“North Park was created by our older generation and it seems horrible to make them and the businesses suffer for bike lanes used by only 1 percent of our city,” he said. He says he wrote the mayor but nothing came of it.

Worried too is Linda Frederick, whose husband owns a real estate property management company, a construction company, and a rental property along the corridor. She says the firm’s tenants worry about parking spaces, especially the younger women who have to walk a distance at night. Workers can’t park near the office; instead, they circle the block trying to time stops to pick up or drop off keys and materials.

Her sister is a retired RN who lives on the property. She is disabled, explains Frederick, because of the years of moving patients.

“When you get rid of disabled people’s parking, it really affects their life,” she said. Now, she adds, her sister chooses not to go out much. The bicycling advocates, she said, are “bullies, if you don’t agree with them, they attack you on social media verbally, they threaten to boycott your businesses, and to put notices on (social media) boards.”.

Handicapped-accessible parking is of concern for advocates like Kent Rodricks, who identifies himself as “a leading San Diego ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) parking activist.” For the disabled, he says “the people creating the bike lanes and parking spaces are able-bodied people who don’t have a clue (nor do they care) about disabled people.”

Pat Sexton and Rodricks says City claims about expanded parking for the disabled are “half-truths.” Sexton says city includes in its count spaces added in its parking structure. Some of the handicapped-accessible parking was moved to side streets, and the total number along the corridor was reduced drastically, Sexton says

Fellow activist Callen added, “It’s hard to pin down the number of ADA spaces spread out around the 30th Street corridor.

The parking spaces for disabled drivers, Rodricks says, “have been relegated to side streets and the ridiculous parking garage four blocks away.

“If I can’t make bus connections, how could I possibly walk to and from a parking garage?” Rodricks said.

In researching the story, we also discovered that the number of bus stops along the corridor have disappeared.

Rob Schupp, director of marketing and communications for the Metropolitan Transit System, says this is the result of MTS’ effort to reduce travel times.

“We eliminated 17 stops within the bike lane project — seven in one direction, seven in the opposite direction between Adams and Juniper,” he said. “Twenty-one stops remain in place, carrying most of the bus passenger traffic for the corridor,” he said.

The office of Council President Pro Tem Stephen Whitburn, whose district includes the 30th Street corridor, was asked to respond to the issues raised by the merchants and residents.

His office staff forwarded a press release from last June, but did not respond to the specific issues now being raised. In that six-month-old release, Whitburn says he “shares their concerns,” adding, “Our city has long failed to sufficiently engage citizens in decision-making.” However, he notes his office didn’t design or develop the project. The councilman suggested the locals get used to the bike lanes as “they need to be well used.”

Callen recalls that when “Whitburn campaigned, he said that the Utah street bike lanes are fine. Why do we need bike lanes on the 30th?”

A similar effort played out in Los Angeles, as part of the city’s “road diet” project, as it is known. A section of Venice Boulevard had a traffic lane removed, which did away with some street parking. And bike lanes were installed.

The promise from those officials was similar to those made by city of San Diego officials — the new bike lanes would create safer conditions for cyclists, improve safety and increase business.

In a story reported on CBS2 and the New Geography website, 21 businesses have closed since the “road diet” was put in place. The 2019 headline read, “When it Comes to Road Diets, Small Businesses are the Biggest Losers.” The web article noted that “You see the same story city after city, neighborhood after neighborhood” in areas as diverse as New York City and Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

J.W. August, a freelance journalist, previously served as a producer with ABC Channel 10 in San Diego. He can be reached directly at jwaugustsd@gmail.com.