CV Councilman Misused Legal Defense Fund to Raise $90,000, Appears to Violate State & Local Laws

Chula Vista politician John McCann used a legal defense fund to recoup legal fees he owed from a 2014 defamation lawsuit he filed – and he appears to have violated state and local election laws by using a legal defense fund to file a lawsuit, not defend one.

State and local elections laws restrict the use of legal defense funds to only pay fees and costs associated with prosecutions or lawsuits filed against candidates or elected officials.

McCann, a registered Republican, ran for election to the Chula Vista City Council in 2014 against former Mayor Steve Padilla, a Democrat. McCann won by only two votes in the November 2014 General Election.

Just weeks before that election, McCann filed a lawsuit against a San Diego labor union claiming one of its campaign mailers was defamatory. McCann, as the plaintiff, named the union, its leader, and its campaign committee as defendants.

The defendants then filed a special motion to dismiss, known as an anti-SLAPP, claiming their campaign literature was protected speech.

SLAPP stands for “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation” and is defined as “.” Anti-SLAPP motions are used to dismiss such frivolous lawsuits.

Although McCann argues he was defending against the motion, the anti-SLAPP only sought to dismiss his lawsuit. There was no cross-complaint or counter suit filed by the defendants.

McCann lost the case when he could not defend the merits of his claims. Defamation claims by public figures or politicians, especially involving political statements made during campaigns, are the most difficult to win and are rarely filed.

The labor union prevailed in its motion to dismiss and the defendants were entitled to legal fees under state law.

LEGAL DEFENSE OR OFFENSE FUND?

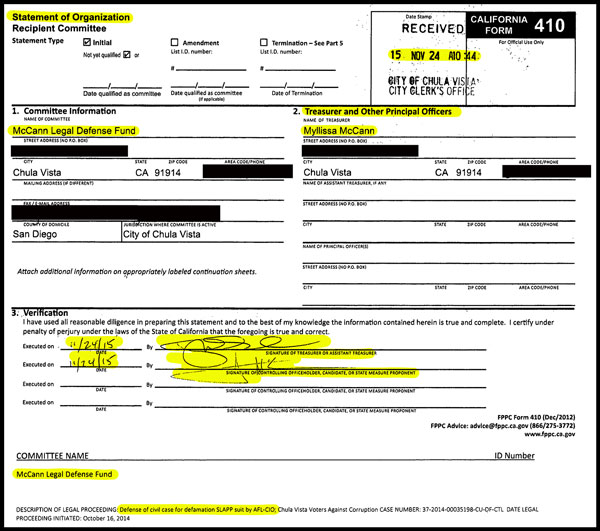

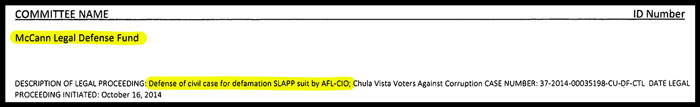

Nearly two months after the Judge ruled against him, McCann opened the “McCann Legal Defense Fund” committee.

McCann’s initial filing, signed under penalty of perjury by both himself and his wife, Myllissa McCann, as the committee Treasurer, states the purpose of the legal defense fund was the “Defense of civil case for defamation SLAPP suit by AFL-CIO”, misrepresenting that his action was a “Defense” instead of an initiation of a lawsuit, but admitting that it was a “SLAPP”, a lawsuit aimed at intimidating or silencing opponents.

State and local laws allows candidates and elected officials to use campaign funds to pay legal fees, but one of only two different paths can be taken.

If candidates choose to use their ordinary campaign committees to pay legal fees, contributions used to pay those fees would be subject to the candidates campaign contribution limits. In Chula Vista, the contribution limits is $350 per person per election and only allowable from a person, not an organization or company.

Or, as McCann did, he can open a separate legal defense fund to solicit and accept contributions for the legal fees and raise contributions without any limits, but there are restrictions on the types of legal fees he can pay.

Most importantly, state campaign regulations specify that a legal defense fund for local candidates, like McCann, can only be used to pay for “Attorney’s fees and other direct legal costs related to the defense of the candidate or officer” and “Administrative costs directly related to compliance” and audits, not for filing plaintiff lawsuits.

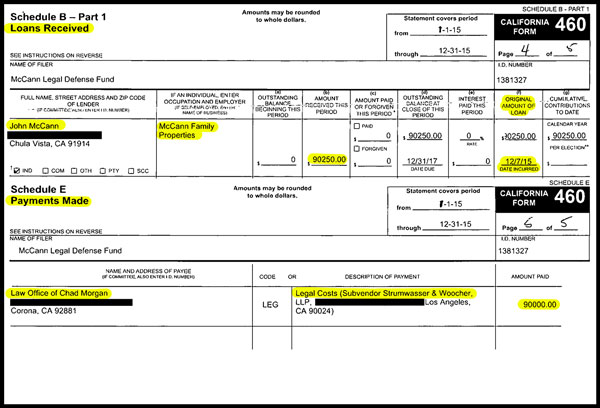

The McCanns loaned the legal defense fund $90,250 from the “McCann Family Properties” then reported a $90,000 payment to “Law Office of Chad Morgan”, a Corona, California-based lawyer who represented McCann in the defamation lawsuit.

Under the payment to Morgan, McCann listed “Sub-vendor Strumwasser & Woocher, LLP“, a high-powered Los Angeles-based law firm that mostly represents Democratic candidates in election and campaign cases.

When contacted this week by La Prensa San Diego, Fredric Woocher, one of the principal partners of the firm, confirmed that his office was paid $90,000 by Chad Morgan, but Court records reveal Woocher actually served as the opposing counsel that represented the labor union defendants in the defamation lawsuit.

The payment to Chad Morgan was actually McCann’s payment of the defendants’ legal costs. The pass-through payment was not properly reported by the McCanns in an apparent attempt to disguise the payment as his own legal fees.

SETTLEMENT OF LAWSUIT SPURS DONATIONS

After the Judge ruled against McCann, the two sides in the lawsuit executed a confidential settlement.

McCann then began to solicit and accept contributions to repay himself his $90,250 loan, and he received 21 contribution between May 2016 until March of this year, ranging from $1,000 to $12,000, including:

$12,000 from Baldwin & Sons, a development company with active projects in Eastern Chula Vista, including parts of the Otay Ranch communities;

$10,000 from Home Fed Corporation, a large land holding company that owns thousands of development acres in Otay Ranch;

$10,000 from Ayres Land Company, owners of the new Ayres Hotel in the Millenia project in Eastlake;

$5,000 from Meridian Communities, a development company building the Millenia project;

$5,000 from Seven Mile Casino, a gambling facility located along the Bayfront that includes a casino, a hotel, and two support buildings on Bay Blvd between E St. and F St.;

$3,500 from Republic Services, the waste company that has the City trash collection contract and also owns the Otay Landfill;

$3,100 from the Chula Vista Police Relief Association, the official non-profit for the Chula Vista Police officers union political action committee;

$2,000 from American Medical Response (AMR), the ambulance company that has an emergency response contract with Chula Vista.

$1,000 from San Diego Associated Builders & Contractors Political Action Committee (ABC PAC), a local trade group representing building contracting companies.

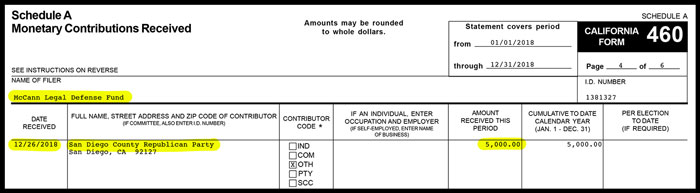

McCann also received three contributions from the San Diego Republican Party: $9,798.67 on November 12, 2016; $5,000 on December 26, 2018; and $4,000 on November 28, 2019.

All of the contributions received into the legal defense fund were for amounts that exceed the City’s $350 campaign contribution limits.

Unlike political campaign contributions that are spent on election expenses, McCann transferred the contributions back to himself to recover the entire amount of his $90,250 personal loan, making him completely whole.

Since the resolution of that lawsuit, McCann has voted on issues directly related to groups that contributed large checks to his legal defense fund, including two contract extensions for AMR, several development approvals for developers that gave contributions, supported police funding increases, and approved Republic Services’ request to raise its trash fees on all Chula Vista customers.

IMPROPER USE OF LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

McCann may have violated state and local campaign laws by using the legal defense fund for legal offense, specifically, to pay legal fees related to his initiation of a lawsuit, not the defense of one.

Under state law, cities can enact more strict campaign finance laws, contribution limits, and other regulations for candidates running in municipal elections.

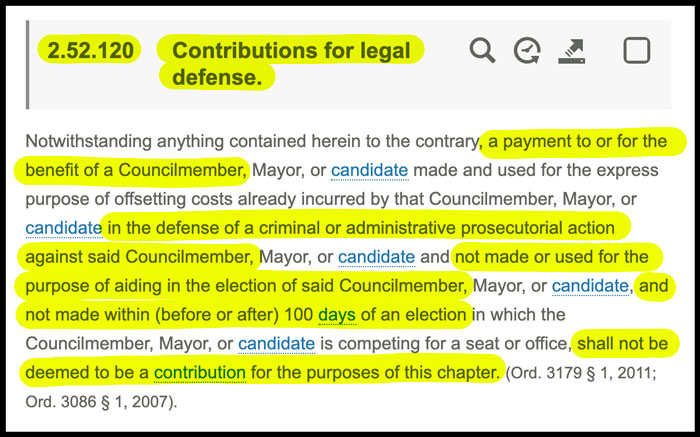

Section 2.52.120 of the Chula Vista Municipal Code (CVMC), titled “Contributions for legal defense“, specifically states that payments given to a candidate or member of the City Council must meet three requirements for them not to be considered campaign contributions, and therefore, not be subject to the City’s campaign finance rules.

Payments made to a candidate or Councilman to be used in “the defense of a criminal or administrative prosecutorial action against said Councilmember“, and “not made or used for the purpose of aiding in the election of said Councilmember“, and “not made within (before or after) 100 days of an election in which the Councilmember, Mayor, or candidate is competing for a seat or office” are exempt from the City’s $350 campaign contribution limit and restriction of having to be from a person, not a company or organization.

All of the contributions received by the McCann Legal Defense Fund would seem to be prohibited under the CVMC because the defamation lawsuit filed by McCann was not a “criminal or administrative prosecutorial action against” him. His lawsuit seems to fall outside of the requirements of the CVMC and, therefore, contributions to the legal defense fund used to pay legal fees relate to filing his defamation case would be prohibited contributions and each would be in violation of the $350 limit and in violation of the ban on contributions from business and organizations.

Additionally, one of McCann’s contributions was a $5,000 check from the San Diego County Republican Party on December 26, 2018, but because McCann appeared on the November 10, 2018 ballot in his re-election campaign, the contribution would be in violation of the Chula Vista Municipal Code’s restriction on legal defense contributions within 100 days before or after an election.

McCann’s own statement on his financial disclosure form that created the McCann Legal Defense Fund seems to show evidence of his intent to misuse the fund. The financial forms must include a description of the legal proceedings covered by the legal defense fund.

On the first filing for the account, McCann and his wife listed “Defense of civil case for defamation SLAPP suit by AFL-CIO”, misrepresenting the case a “defense” when he clearly was initiating the lawsuit.

That case is listed in San Diego Superior Court records as “John McCann vs. San Diego Building and Construction Trades Council, AFL-CIO“.

The legal defense fund was created in November 2015, nearly two months after the Judge had already ruled against McCann. At that point in time, McCann already knew he owed the legal fees and could have paid them directly to the lawyers from his personal bank account, but instead, created the legal defense fund to begin to solicit and accept contributions.

MCCANN’S OTHER LEGAL CASE

After a vote recount upheld McCann’s two-vote victory in 2014, a local resident, Aurora Clark, sued to challenge the election outcome because the County Registrar of Voters disallowed some votes that she believed should have been counted and could have changed the outcome of the election.

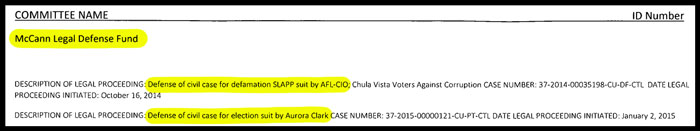

In December 2015, the McCann’s amended the legal defense fund paperwork to add Clark’s election challenge lawsuit, and described it as “Defense of civil case for election suit by Aurora Clark“.

The case is listed in San Diego Superior Court as “Aurora Clark v. John McCann“.

McCann described the case using the same words of “Defense of civil case” as he did in the labor union defamation case; however, in this case, he accurately described it as defensive since he was the defendant in the case filed by Clark, unlike the defamation case he filed as a plaintiff. Both cases were made to appear to be lawsuits filed against McCann.

McCann won the election challenge lawsuit. The Court awarded McCann reimbursement of all legal fees he sought: $99,918. In that case, McCann was made whole by the plaintiff. Clark’s attorneys submitted payment of those fees to McCann’s lawyers in June 2016.

Since McCann was reimbursed for the legal fees he incurred in defense of the Clark case, he could not raise contributions to recover those fees.

PENALTIES FOR VIOLATIONS

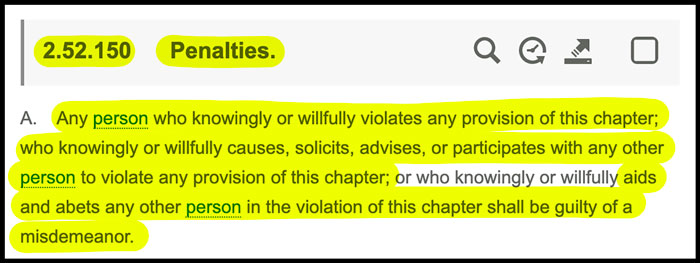

Both state and the Chula Vista Municipal Code describe violations of campaign finance laws as misdemeanors, punishable by fines and/or imprisonment in jail, or both, for each occurance.

CVMC specifically states that “Any person who knowingly or willfully violates any provision of this chapter; who knowingly or willfully causes, solicits, advises, or participates with any other person to violate any provision of this chapter; or who knowingly or willfully aids and abets any other person in the violation of this chapter shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.

Both McCann and his wife, who signed the legal defense documents under penalty of perjury as the Treasurer, could be guilty of the violations.

Also under the CVMC, all prohibited contributions must be returned by the candidate. Accordingly, the McCanns may have to return all of the prohibited contributions to the original donors.

State elections code also states that violations of campaign finance regulations can be tried as misdemeanors.

The Chula Vista Municipal Code outlines a process for investigating alleged violations of local ordinances, and specifically allows for an independent law firm to serve as the Enforcement Authority to recommend appropriate actions that could include civil or administrative actions, or referral to the District Attorney for prosecution.

In addition to the City process, the San Diego County District Attorney’s office can directly investigate local campaign finance violations.

The California Fair Political Practices Commission (FPPC) could also investigate allegations of violations of state elections laws.

RESPONSES FROM MCCANN & MORGAN

McCann responded to several requests for comment related to his campaign committee, but did not provide a clear response when asked about legal fees he incurred and recovered.

“We were awarded partial legal fees by the court; however additional legal expenses were not recovered and these expenses were recovered in accordance with state law through the legal defense fund,” McCann wrote.

McCann’s comments ignored his defamation lawsuit and he purposely conflated the lawsuits to disguise the fact that he raised contributions to repay his own loan related to legal fees he incurred in his defamation case, not the election challenge and appeal. He did not respond

Chad Morgan also provided comments when asked about his work on McCann’s campaign, but stopped responding when asked about his legal representation. He did not respond to follow-up questions about his legal work and fees.

Alberto Garcia

Alberto Garcia