PART II: CV Councilman Received $40k in Unpaid Literature from Two “Companies”

John McCann, a long-time Chula Vista Councilman, accepted over $40,000 in unpaid campaign literature from two entities who went unpaid for more than a year after the election, apparently in violation of the City’s campaign finance laws.

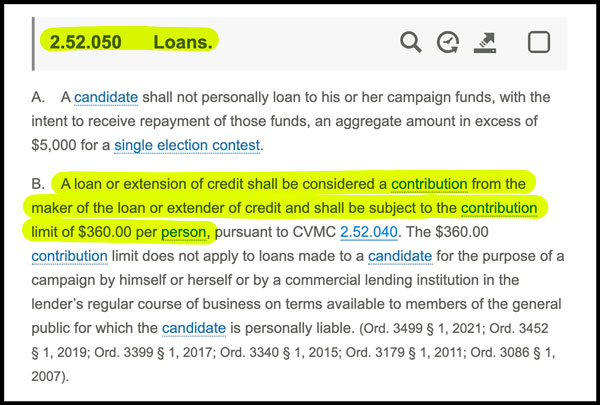

The City’s Municipal Code defines “a loan or extension of credit” as a campaign contribution subject to the limit of $300 and only permissible from a person, not a company or entity.

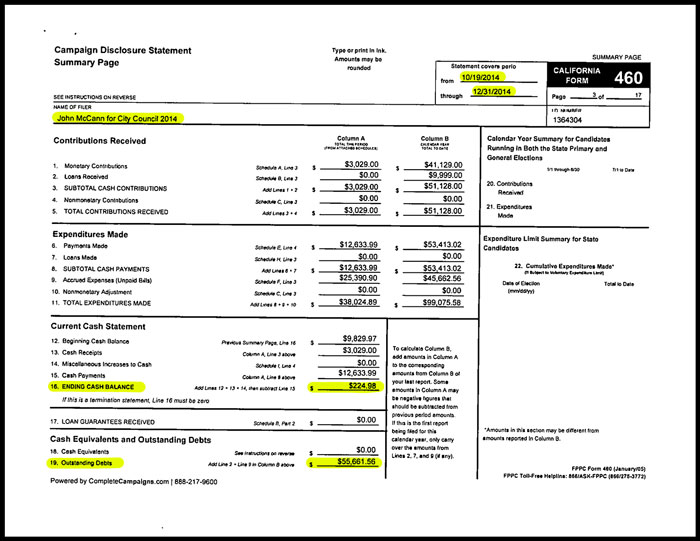

McCann’s official campaign disclosures reported he ended the campaign with only $224.98 on hand, but $55,661.56 in debt, including $9,999 due to himself for loans he made to his campaign, a $5,000 “win bonus” due to his political consultant after his victory, and $40,662.56 in unpaid invoices from entities that fronted the printing, mailing, and postage costs for campaign literature.

McCann won the election by only two votes.

The expenditures occurred during McCann’s 2014 election for City Council where he sought to return to Citywide elected office after having previously served eight years on the Council then four years on the Sweetwater Union High School District.

The City’s term limits restrict someone from serving more than two consecutive terms, but the limits are reset if the person stays off the Council for at least one election cycle. McCann had first been elected in 2002 and re-elected in 2006 before he was elected to the school board in 2010.

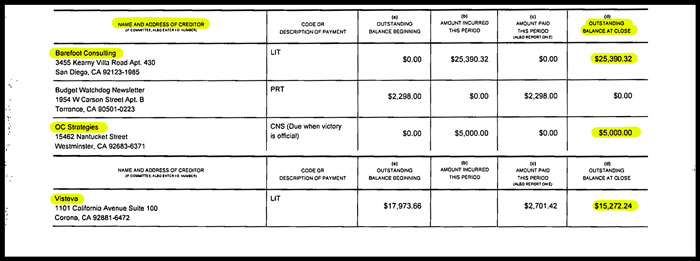

In the 2014 campaign, McCann disclosed receiving $24,973.66 in campaign literature from “Visteva” with an address in the city of Corona, California, but only paid $7,000 of those expenses before the election ended, leaving an unpaid balance of $15,272.24.

Visteva’s address is within a shared executive suite of offices, and the entity does not seem to be a printing or mailing company. No listing was found for Visteva online or in the Riverside County Assessor’s office that maintains filings for fictitious names, or DBAs.

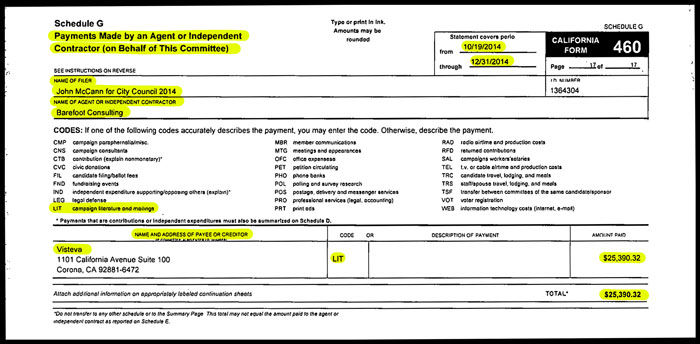

Visteva was also listed on McCann’s campaign disclosures as a sub-vendor to another entity, Barefoot Consulting, with an address listed at a residential apartment complex in Kearny Mesa. Barefoot Consulting does not appear in online searches or registered with the San Diego County Recorder’s office that issues fictitious business names.

McCann also disclosed receiving $25,390.32 in unpaid campaign literature from Barefoot Consulting. Although Barefoot Consulting was not paid by McCann at the time it provided the literature, Barefoot Consulting reported paying Visteva the same amount of $25,390.32 for campaign literature.

Barefoot Consulting did not appear to have made any money on the transaction, but seems to have provided the money for the mailings. It is not clear from the filings what role, if any, Barefoot Consulting played in McCann’s election.

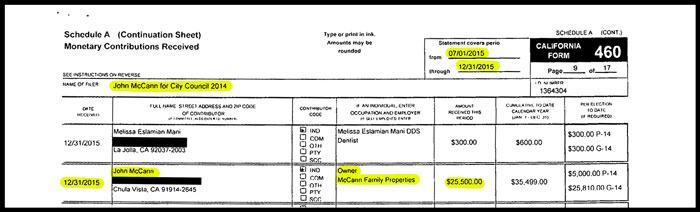

The nearly $41,000 in outstanding invoices to Visteva and Barefoot Consulting remained unpaid for more than 14 months until McCann donated $25,500 to his own campaign fund on December 31, 2015, and used the money and other donor contributions to pay the outstanding invoices.

WHO WAS BEHIND “COMPANIES”

McCann’s official filings do not disclose the names of any principals behind either of the two entities, but online searches revealed some connections.

Barefoot Consulting shared its address with Brad Henson, a Republican political consultant who worked on several campaigns in the San Diego area before moving to Texas. Henson did not own a printing business in 2014. McCann should have listed all sub-vendors used by Barefoot Consulting, but failed to do so. There is no record of how much of Barefoot’s billings were passed on to other vendors.

Visteva shared its address with Chad Morgan, another Republican political consultant who is also a lawyer. Morgan previously served as staff to a member of the California State Assembly and managed political campaigns. News articles from that time show Morgan as the owner of Visteva.

Morgan’s entity Visteva is not a printing and mailing services company, and presumably would have had to pay a sub-vendor to print and mail the literature for McCann, but he did not properly list any sub-vendors.

EXTENSION OF CREDIT

The Chula Vista Municipal Code states that ““, which was $300 at the time of the 2014 election.

Although other cities provide for some period of time to pay outstanding invoices for services, Chula Vista defines any extension of credit as a contribution without any time to make the payment. Although revolving bills like cell phone and utilities are billed monthly and paid shortly after receiving the bills, campaign printing and mailing services are not usually provided on a billing basis.

Accordingly, most campaigns pay for mailing literature before the mail is delivered because printing and mailing companies understand it my be difficult to collect payment after the election, especially from a losing campaign or candidate.

In McCann’s case, his campaign did not have sufficient money on hand to pay for the mailings at the time the literature was mailed before Election Day, proving that the delivery of campaign materials without payment had to have been an extension of credit.

McCann’s financial disclosure report covering the period of the election on November 4, 2014, and through the end of that year, show his campaign fund only had $224.98 on hand, and $55,661.56 in debts.

In preparation for this article, La Prensa San Diego sent McCann 13 questions regarding the unpaid expenses paid by Visteva and Barefoot Consulting and his understanding of the City’s Municipal Code relating to campaigns.

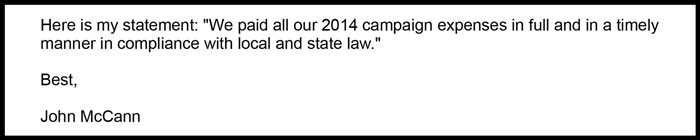

“We paid all our 2014 campaign expenses in full and in a timely manner in compliance with local and state law,” is all McCann wrote.

DEBTS VS UNPAID BILLS

The Chula Vista Municipal Code (CVMC) does allow debt and loans, but both have rules and limitations.

Under the CVMC, McCann could loan himself up to $5,000 per election contest, meaning each of the Primary and General Elections, with the expectation of being repaid. The code also allows for individuals, not companies or entities, to make loans to a campaign up to the contribution limit and still be able to be repaid.

The candidate could then raise contributions to repay such loans without any stated timeframe to retire such debt.

McCann did, in fact, loan his 2014 campaign $5,000 in the Primary and $4,999 in the General Election.

But an extension of credit is described in the CVMC as contribution and subject to the City’s limits, including the dollar amount and that it can only be from a “person” not an “organization” defined by the CVMC as “a proprietorship, labor union, firm, partnership, joint venture, syndicate, business, trust, company, corporation, association, or committee, including a political action committee.”

McCann’s solicitation and acceptance of campaign literature without the means to pay for them would be an extension of credit, and having received the goods and services from an entity and having a value of more than the contribution limit would make them “prohibited” contributions under the CVMC, requiring McCann to return the contributions and also subjecting him to prosecution as either a misdemeanor or administrative fine for each offense.

The Chula Vista Municipal Code sections related to campaign contribution limits, definitions, and restrictions on legal defense funds were first put in place in 2007 and amended several times since then to adjust the contribution limits from $300 to now $360.

In January 2016, La Prensa San Diego published a story about McCann’s debt in his 2014 campaign just weeks after he had finally paid off the outstanding invoices for the literature. At the time of the article, however, La Prensa San Diego did not discover the connections between McCann, Morgan, and Henson.

LAWSUITS & LEGAL FEES DON’T ADD UP

The 2014 election between McCann and then-former Mayor Steve Padilla ended so closely that a re-count was initiated. Several ballots were rejected over issues of residency, and McCann ended with an official victory of only two votes, but the fighting was not yet over.

Three weeks before the election, McCann filed a defamation lawsuit against a local labor union, its leader, and its campaign political action committee claiming that one of their mailers accused McCann of having committed a “felony” when he served on the Sweetwater School board. Defamation claims by elected officials, especially during a campaign, are very difficult to prove and are rarely even filed.

McCann hired Chad Morgan as his lawyer to file the lawsuit. Morgan was the owner of “Visteva” that had provided the unpaid campaign literature to McCann’s campaign just months earlier. At the time McCann hired Morgan as a lawyer, McCann still owned him nearly $18,000 in unpaid campaign literature expenses.

In defending themselves from McCann’s lawsuit, the union filed a motion to dismiss, known as an anti-SLAPP motion, a usual tactic filed in response to lawsuits that attempt to chill public criticism of public officials. SLAPP stands for Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation.

The union defendants won their motion and had the case dismissed. Under state law, the prevailing party was entitled to reimbursement of their legal costs by the losing party, McCann.

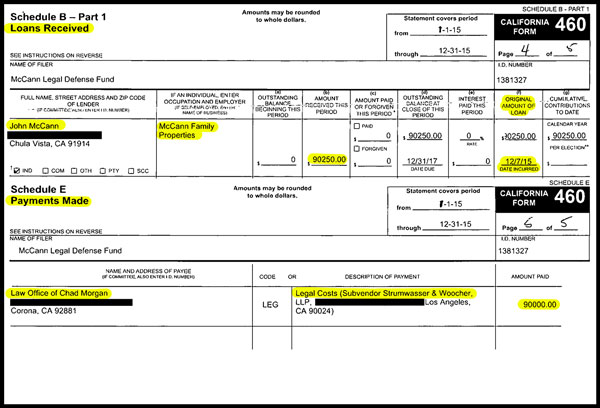

Within weeks of the Judge’s ruling against him, McCann opened the McCann Legal Defense Fund and loaned it $90,250 from his “McCann Family Properties”.

In official filings for the McCann Legal Defense Fund, Morgan is listed as having been paid $90,000, but passed the entire amount on to the lawyers representing the labor union after McCann lost his case and owed the defendants’ legal fees.

According to McCann’s reports, Morgan was not paid for his legal services and, therefore, must have provided his legal representation as a volunteer to McCann’s campaign with no expectation of payment or McCann paid him directly without using the Legal Defense Fund.

Just weeks after McCann’s victory was confirmed by the San Diego County Registrar of Voters in December 2014, a local resident, Aurora Clark, filed an election challenge lawsuit claiming several ballots were disallowed which could have changed the outcome of the election.

That case eventually went to the Appellate Court which ruled in McCann’s favor. The plaintiff was ordered to reimburse McCann $99,918 in legal fees, exactly what he had requested in court. McCann received the legal fees reimbursement in June 2016.

In his Legal Defense Fund filings, McCann only listed one payment to the law firm that handled the Clark case: a payment of $9,798.87, not the $99,918 the law firm and McCann claimed in sworn court filings. It is not clear from McCann’s official filings if he paid that law firm directly from his own funds without running it through the legal defense fund, or if he failed to properly report the remaining $90,000 he spent on legal fees before he was reimbursed by Clark.

RAISED MONEY FROM INTERESTED PARTIES

McCann then used the Legal Defense Fund to raise $90,000 to repay his own loan made to the fund. Between May 2016 and March 2021, McCann solicited and accepted 21 contributions totaling nearly $100,000 from various developers, companies, and individuals who had interests before the City Council.

In several cases, McCann voted on the City Council to approve projects, contracts, and requests from companies and individuals who made contributions to the Legal Defense Fund. Specifically, McCann received contributions including:

$12,000 from Baldwin & Sons, a development company with active projects in Eastern Chula Vista, including parts of the Otay Ranch communities;

$10,000 from Home Fed Corporation, a large land holding company that owns thousands of development acres in Otay Ranch;

$10,000 from Ayres Land Company, owners of the new Ayres Hotel in the Millenia project in Eastlake;

$5,000 from Meridian Communities, a development company building the Millenia project;

$5,000 from Seven Mile Casino, a gambling facility located along the Bayfront that includes a casino, a hotel, and two support buildings on Bay Blvd between E St. and F St.;

$3,500 from Republic Services, the waste company that has the City trash collection contract and also owns the Otay Landfill;

$3,100 from the Chula Vista Police Relief Association, the official non-profit for the Chula Vista Police officers union political action committee;

$2,000 from American Medical Response (AMR), the ambulance company that has an emergency response contract with Chula Vista which has been renewed twice in the past 6 years; and,

$1,000 from San Diego Associated Builders & Contractors Political Action Committee (ABC PAC), a local trade group representing building contracting companies.

McCann also received three contributions from the San Diego Republican Party: $9,798.67 on November 12, 2016; $5,000 on December 26, 2018; and $4,000 on November 28, 2019.

All of the contributions received into the legal defense fund were for amounts that exceed the City’s $350 campaign contribution limits.

PROHIBITED CONTRIBUTIONS

La Prensa San Diego recently published a story about McCann’s seemingly illegal use of a legal defense fund to pay fees incurred after initiating a lawsuit, not defending one.

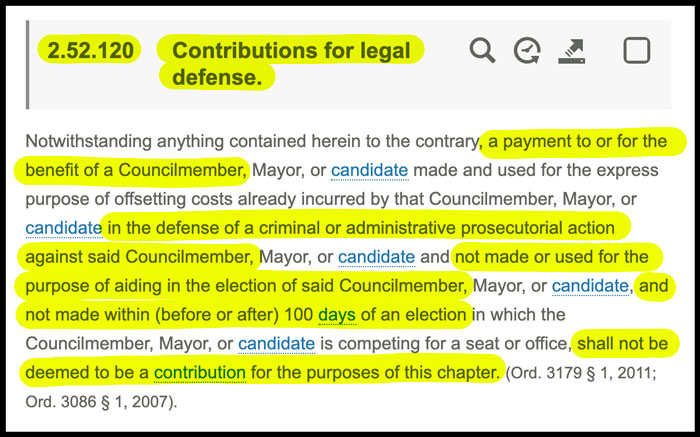

The Chula Vista Municipal Code specifically defines contributions to a legal defense fund and they must meet three criteria in order to avoid the usual campaign contribution limits.

McCann’s expenditure of legal defense funds to pay attorney’s costs incurred in a plaintiff lawsuit would not meet the City’s requirement that it be only for “the defense of a criminal or administrative prosecutorial action against said Councilmember” because his plaintiff lawsuit for defamation was offensive, not defensive.

Unlike political campaign contributions that are spent on election expenses, McCann transferred the contributions back to himself to recover the entire amount of his $90,250 personal loan, making him completely whole.

Since the resolution of that lawsuit, McCann has voted on issues directly related to groups that contributed large checks to his legal defense fund, including two contract extensions for AMR, several development approvals for developers that gave contributions, supported police funding increases, and approved Republic Services’ request to raise its trash fees on all Chula Vista customers.

McCann did not respond to additional questions from La Prensa San Diego specifically related to the legal costs incurred in the lawsuits and his votes on issues related to those who contributed large checks to his legal fund.

Alberto Garcia

Alberto Garcia