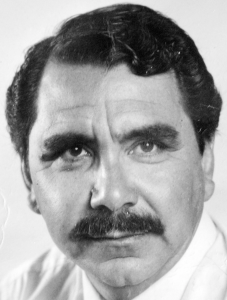

ERNESTO MARTIN BARRERA: December 12, 1935 – February 6, 2018

It is slightly less than three-thousand miles between the tiny village of Mompos, Colombia, and Washington, D.C. But of course, it is in many ways farther then traveling to the moon.

On a bright day in early 1961, my father, Ernesto Martin Barrera and sixteen other Colombian college students, made the trip to America as part of a visiting tour of young leaders. They got to shake hands with a young American president who had his own dreams of trips to the moon, and they got to tour America.

Each was given a pocket-copy of Alexis de Tocqueville’s book, Democracy In America. They met Congressmen and dignitaries who practiced their Spanish with the men as they traveled the United States.

They were featured in small, local newspaper articles and shown the trappings of America – from the Liberty Bell and Constitution Hall in Philadelphia, to the Statue of Liberty in New York’s Harbor, to the St. Louis Archway. Ultimately, they even got to see Hollywood.

On the final leg of the journey, my Dad met a young UCLA Spanish and Art student of Scandinavian, German, and Irish heritage by way of Brooklyn. Her name was Marion Kathryn Holmes. By all accounts and family lore, it was love at first sight for both, despite the fact that my Brooklyn Dodger fan mother had difficulty listening to my father repeatedly talk with awe of “Meek Mant-le” and the New York Yankees.

Though he traveled back to Colombia to complete his law degree, after that meeting it was never in doubt that they would marry.

The following year, Marion flew down to Colombia to be with him, and on August 25, 1962, they were married. My father graduated from the University of Cartagena Law School and began a short stint serving as a local judge.

In the Spring of 1963, they moved back to the United States and that June, I was born. My father began his teaching career at UCLA and his studies in Spanish and Portuguese Literature, and Theater, at USC.

My brother Richard was born in 1966.

My father became a United States citizen in 1967. He received his PHD from USC early in 1970, six months after he was hired by President Malcolm Love as professor of Spanish and Latin American studies at San Diego State College.

My brother Douglas was born in 1972, and that same year we moved into our home. When our dog, Squirt, was adopted in Spring 1974, our family was complete.

My father made sancocho y platano a couple times per year, and once a week would make his own rice and beans dish, along with the frequent scrambled egg burritos for Sunday morning breakfast. We had open-house nights at school, and annual trips to Disneyland. We went out on Halloween for trick-or-treating, and summer picnics at the beach – Dad loved to barbeque during the summer.

Nobody loved Christmas mornings or birthdays more then my father. He would get the biggest, sweetest smile of anyone I have ever seen when excited about opening a present – either given to someone, or when given to him.

One year on Christmas Eve when I was eight, my mother sent us to bed around 10 p.m. only to have my father wake us up a little after midnight because all the presents from “Santa” had been placed under the tree and he was too excited to wait until morning to see us open them up.

My father loved and understood baseball better then anyone I have ever known. We always said he missed his true calling by not working with Jerry Coleman as a Padres play-by-play announcer.

In fact, the only time he would ever sneak away from his office during a work week was when a fellow professor and buddy of his would show up with two tickets to an afternoon Padres game.

He took all three of his sons to our first games (I still have a METS pennant from that first game I saw – the new expansion team San Diego Padres versus the 1969 “Miracle Mets”).

Whether it was watching Mickey Mantle hit a 500-foot home run, watching Sandy Koufax pitch a no-hitter, to Willie Mays play centerfield, to Roberto Clemente run the bases, to Tony Gwynn slap a grounder to the opposite field, he was a baseball fan in the purest sense.

He loved the game – the living chess match between the managers. The brilliant athleticism and grace of the players. The manliness of baseball players and a sport where a player doesn’t brag when he does something spectacular and doesn’t cry when he gets hurt. Just spray a little ice on the wound and get back to baseball.

They’re professionals. They’re supposed to do the impossible.

My father understood politics – not to the same extent as baseball – but with equal enthusiasm. I’ll always remember his rants against Richard Nixon during the Watergate scandal, and his admiration for Judge John Sirica, who upheld the rule of law and demonstrated better then anyone our wonderful American Constitutional system.

For my 13th birthday, my father tried to take me to see “All The President’s Men”, but I insisted we see “Rocky” instead. He loved “Rocky” and that became something of a tradition for my birthday.

The following year he took me and Douglas to see “Star Wars” and the year after that it was “Superman.”

For all his intellectual energy and tastes, his favorite show was “The Streets of San Francisco” and he enjoyed a good western or a James Bond marathon. In later years he got to the point where he could recite dialogue from John Wayne’s “El Dorado.”

San Diego State College became San Diego State University in the early 1970’s, and, for three decades, my father became a leader in the study of Spanish and Latin American Literature.

He served as a member of the SDSU faculty Senate for over two decades, and was Chairman of the SDSU Spanish Department for 15 years.

During that time, he organized literary symposiums that attracted the leading novelists and scholars of modern Spanish and Latin American Literature from around the world. He earned his full professorship younger and faster then most, and he wrote and published peer-reviewed articles and books on his literary ideas, specifically his book on Colombian playwright Luis Enrique Osorio titled Realidad y Fantasía en el Drama Social de Luis Enrique Osorio.

He never missed a single day of work in 30 years at SDSU, and beyond anything else, he loved to teach.

At the beginning of every semester, you could see the excitement in his face as he prepared for new classes.

He enjoyed being around the students. He prepared for the Fall 1997 term (what would be his final semester) with the same energy he’d prepared for teaching his first semester in the Fall of 1969.

He loved teaching more then any other aspect of his career. He taught all levels from introductory Spanish courses to mentoring the graduate students seeking their own Master and PHD credentials.

He never missed an opportunity to teach during Winter and Summer sessions, finding his work and the environment of intellectual life much more fulfilling or relaxing then he ever did when on a vacation.

Some people are defined by their jobs and others simply see their work as a means to making money.

My Dad was the former – in every way imaginable. He was a Professor. He lived and breathed the world of books, ideas, and philosophies.

When he suffered a terrible stroke in 1997, that world came crashing to a halt. He’d never missed a day of work and all of sudden, he would never work again, but it was in those first weeks and months after that stroke, that I saw the man I really never knew.

We were not close. We had our fights. Big fights. And through most of my early life and into my 30s, we didn’t have a lot of use for each other.

I was a dissapointment to him and vice-versa . He had a hard life growing up in Colombia – unforgiving in the cultural and societal environment of his youth.

Drinking played a major role in his concepts of manhood and it got the better of him outside of work most of his adult life. It certainly was what caused his poor health later on in life.

But, in the aftermath of that stroke – in his determination to regain his life – he did not submit to fear. He did not allow frustration to deter him.

He began the process of re-learning to read, teaching himself to move and use his brain so he could drive a car again. He wanted to go back to work. He had fought all his life to make his own way. He’d never been dependent on anyone and he’d always been his own man.

Though the stroke robbed him at the age of 62 from ever returning to the classroom, he never once surrendered to the despair of what had happened. There was never a moment of self-pity – though that stroke earned him more than a few of those moments. He simply did his best.

When he was recovering in the hospital, I visited him every day. It was a bigger surprise to me than anyone how hard the thought of my father dying hit me. I cried more then once. I went into the hospital chapel and prayed, asking God for 20 more years with my Dad.

As he recovered from that first stroke, every morning I would clean the right side of his mouth of the food not swallowed from the night before. I’d brush his teeth and shave him because I knew Dad’s sense of well-being was based on those simple daily rituals of grooming; a man respects his appearance.

I took him to get his first shower three weeks after that stroke. He cried, which the doctor said was a typical response to feeling normal again after a person has been though something traumatic.

It was my chance to finally be there and do something that mattered in his life. I don’t know if he really remembered much of it, but it mattered to me, and I know it helped his recovery.

He became my Dad in those weeks and months following the stroke, and for a short while, it seemed he might actually return to his old life.

But it was not to be; in 2009, a second stroke confirmed what the fist one had determined, that he was retired from his work and the life he loved.

His humor and love for baseball, politics, and family sustained him in the years that followed. But, the terrible nature of sickness and age whithered him down, with each passing year taking him farther away from his former self.

In the end, he was a shadow of the man he’d always been to countless thousands of students and others who knew him, respected him, and loved him.

My father was a man of education. His favorite author was Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and I am tempted to conclude this remembrance of my Dad with something from One Hundred Years of Solitude. But, it is de Tocqueville’s work that seems to me more appropriate:

“From the time when the exercise of the intellect became the source of strength and of wealth, it is impossible not to consider every addition to science, every fresh truth, and every new idea as a germ of power placed within the reach of the people. Poetry, eloquence, and memory, the grace of wit, the glow of imagination, the depth of thought, and all the gifts which are bestowed by Providence with an equal hand, turned to the advantage of the democracy; and even when they were in the possession of its adversaries they still served its cause by throwing into relief the natural greatness of man; its conquests spread, therefore, with those of civilization and knowledge, and literature became an arsenal where the poorest and the weakest could always find weapons to their hand.”

Now that my Dad’s suffering is over, I have no doubt he is enjoying a good book and a glass of wine.

Soon, he will watch the ultimate All-Star Game. Roberto Clemente will catch, turn, and rifle a ball from deep right-center to home plate for the out; Tony Gwynn will smack yet another surgically placed hit through the infield; and most of all, “Meek Mantle” will hit one out of the park that never seems to come down.

My Dad is arguing politics with anyone around him while enjoying a great barbeque on a warm summer’s day.

And, as he watches his wife, sons, and grandchildren continue in a world now lonelier without him, he has a big, sweet smile on his face because he knows what a special gift his life was to all who knew him.

So long, Dad.–