Killing Spree on the Border

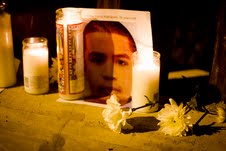

His name was José Antonio Elena Rodriguez. At 16, he was just finishing junior high and living with his grandmother on the Mexican side of the border city of Nogales.

On October 13, 2012, José Antonio was hit by a hail of bullets coming from the U.S. side of the metal fence that lacerates Nogales. Some seven shots penetrated the boy’s body through the back and the head. He died instantly.

Sitting in a busy coffee shop in Nogales, Taide Elena, Jose Antonio’s grandmother, shows a photo of her grandson. She breaks down when she talks about the dreams “Toñito” had.

“He wasn’t even on the line. He was just walking on the sidewalk, three blocks from his house,” she sobs as she recalls the night he was shot. “Why did they carry out this cruel assassination?”

The shots were fired by U.S. Border Patrol agents. The Border Patrol claims that the youth threw rocks at the unidentified agent or agents, who fired in return. The family reports that neither they nor their lawyer nor Mexican authorities have received information from the investigation on the U.S. side. As conflicting versions of the story circulate, the Border Patrol will not even release the names of the agents under investigation.

The Border Patrol authorizes its agents to respond to rock-throwing with lethal force. This is not the first time BP agents have fired on Mexico and killed young men for allegedly hurling stones toward the border.

The Southern Border Communities Coalition has registered 19 cases of people killed by the Border Patrol just since 2010. The Coalition, formed in March of 2011, brings together more than 60 organizations in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas to “Ensure that border enforcement policies and practices are accountable and fair, respect human dignity and human rights, and prevent the loss of life in the region.”

On December 2, another person was shot to death by the Border Patrol 12 miles northwest of Sasabe, Arizona, in a killing that apparently would not even have been made public had an enterprising Tucson reporter not followed up on an anonymous tip. Add to that the incident on October 25, when Texas State Troopers in an armed helicopter fired into a truckload of immigrants, killing two Guatemalans, and the toll reaches 22 known cases.

The numbers themselves justify calling this a killing spree. The Border Patrol may contend that some of these killings were accidental, but in the current war-zone mentality among U.S. border security forces, it seems to matter little who died or how.

Mexico’s Foreign Relations Department issued a statement following Jose Antonio’s shooting calling such deaths “a serious bilateral problem.” The violence has even attracted the attention of Navi Pillay, the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, who declared that the numerous reports of young people killed at the border show “excessive force by the U.S. border patrols.”

The media turns its attention to what’s happening only sporadically, when someone is killed. But the problem of Border Patrol violence appears to be endemic. The U.S. human rights group No More Deaths issued a report last year called “Culture of Cruelty,” in which it noted 30,000 cases of abuse by the Border Patrol between November 2008 and March of 2011.

Other human rights groups have issued reports and presented grievances to international organizations, and the Mexican government complains briefly every time a Mexican is killed. But the deaths and abuses keep mounting.

Border Injustice

Not only are Mexican teens being killed by U.S. security forces on the border. Their deaths are usually not punished. An investigation by the Arizona Daily Star found that U.S. border agencies announce investigations and then frequently seal them off from public scrutiny. Often what happens is that months or years later they quietly announce years that their agents have been cleared of all charges and the case is closed.

During the same period studied by the Southern Border Communities Coalition, four Border Patrol agents were killed on duty in Arizona. Their deaths are as lamentable as those of the Mexicans and Guatemalans killed by other agents. But the response of U.S. government officials and the justice system to their deaths has been entirely different.

Border Patrol officer Brian Terry was killed in a shoot-out in December 2010. Mexican authorities picked up two suspects, one of whom confessed. Terry’s death became a cause celebré among the Obama administration’s critics when it was revealed that he was murdered by weapons “walked” across the border to criminals under a U.S. government program called “Fast and Furious.” His relatives filed a wrongful death claim against those responsible for the program in February.

When Border Patrol agent Nicholas Ivie was killed on October 2 this year, the Mexican government again responded quickly, picking up two suspects within days. Apparently, too quickly. This eagerness to respond was soon called into question when the FBI reported that its preliminary findings showed that Ivie had been killed by “friendly fire”—that is, by a fellow Border Patrol agent whom he had shot in apparent confusion.

Arizona governor Jan Brewer came out on October 2 with a public statement seeking to use the fateful shooting to criticize the federal government for failing to support even more “security” on the border. “This ought not only be a day of tears,” she said. “There should be anger, too. Righteous anger—at the kind of evil that causes sorrow this deep, and at the federal failure and political stalemate that has left our border unsecured and our Border Patrol in harm’s way. Four fallen agents in less than two years is the result.”

The two other agents were killed when they ran their patrol car into a freight train while chasing alleged drug traffickers.

So of the four agents, one was killed by another agent, one by U.S. weapons, and two more when they crashed their car into a train. With the exception of Terry, their violent deaths were not the direct result of “evil” Mexican smugglers, and much less of “federal failure” to secure the border.

The contrast in the official responses to the killings of U.S. agents and of Mexicans, and the muddled circumstances of the agents’ deaths, reveals some of the deep contradictions in U.S. border security policies. The agents were “placed in harm´s way” not due to “insecure borders,” but as a direct result of excessively violent and careless U.S. border security policies. When we add the 22 mostly unarmed Mexicans shot or beaten to death in circumstances that have never been fully revealed, these policies appear not only wrong but also criminal.

Lethal Force

“It’s not fair that they take the life of a boy,” says Elena, in tears. “They’re not animals; they’re killing human beings, people with a right to live. Do they think that just because they have a gun and a badge they can do whatever they want? Or maybe they think by doing this they’ll be heroes in the United States?”

The Border Patrol’s use of lethal force became a major issue two years ago, when Sergio Hernandez, another Mexican teenager, was killed when the Border Patrol fired shots across the border into Ciudad Juarez. Months later, the Border Patrol decided not to charge the agent who killed the boy. Hernandez’s family, understandably upset, has decided to sue the agent who killed him. The U.S. government has refused to turn over video evidence that could clear up what really happened, despite the legal proceedings.

Two and a half years after Sergio was killed in Ciudad Juarez and two months after José Antonio’s death, the U.S. government has finally called for a review of the rules regarding the use of lethal force on the border.

Border Patrol policies seem to justify the use of lethal force in virtually any situation deemed necessary by often skittish agents with impossible mandates, inadequate training, and racist beliefs; the decision to review them is certainly a step in the right direction. The next steps must include rules for making information available to the public, Mexican authorities, and affected families and communities; full and open investigations; prosecution, rather than cover-ups, of those found guilty of fatal and non-fatal abuses; and a new policy that significantly restricts the use of firearms.

Most importantly, unproven and ill-defined “national security” objectives must never be used to deny basic human rights, including the right to life. A real commitment to security must place human life and public safety above all else—no matter which side of the border you’re on.