March is National Women’s History Month

Women’s Education – Women’s Empowerment is the theme for National Women’s History Month 2012

Although women now outnumber men in American colleges nationwide, this reversal of the gender gap is a very recent phenomenon. The fight to learn was a valiant struggle waged by many tenacious women — across years and across cultures. After the American Revolution, the notion of education as a safeguard for democracy created opportunities for girls to gain a basic education. However, that education was based largely on the premise that, as mothers, they would nurture the minds and bodies of the (male) citizens and leaders. This idea that educating women meant educating mothers endured in America for many years at all levels of education.

Pioneers of secondary education for young women faced arguments from physicians and other “experts” who claimed either that females were incapable of intellectual development equal to men, or that they would be harmed by striving for it. Women’s supposed intellectual and moral weakness was also used to argue against coeducation, which would surely be an assault on purity and femininity. Emma Willard, in her 1819 Plan for Improving Female Education, noted with derision the focus of women’s “education” on fostering the display of youth and beauty, and asserted that women are “the companions, not the satellites of men” — “primary existences” whose education must prepare them to be full partners in life’s journey.

While Harvard, the first college chartered in America, was founded in 1636, it would be almost two centuries before the founding of the first college to admit women—Oberlin, which was chartered in 1833. And even as “coeducation” grew, women’s courses of study were often different from men’s, and women’s role models were few, as most faculty members were male. Harvard itself opened its “Annex” (Radcliffe) for women in 1879 rather than admit women to the men’s college—and single-sex education remained the elite norm in the U.S. until the early 1970s. As coeducation took hold in the Ivy League, the number of women’s colleges decreased steadily; those that remain still answer the need of young women to find their voices, and today’s women’s colleges enroll a far more diverse cross-section of the country than did the original Seven Sisters.

The equal opportunity to learn, which today is taken for granted, owes much to Title IX of the Education Codes of the Higher Education Act Amendments. Passed in 1972 and enacted in 1977, this legislation prohibited gender discrimination by federally funded institutions. Its enactment has served as the primary tool for women’s fuller participation in all aspects of education from scholarships, to facilities, to classes formerly closed to women. It has also transformed the educational landscape of the United States within the span of a generation.

Each year National Women’s History Month employs a unifying theme and recognizes national honorees whose work and lives testify to that theme. This year we are proud to honor six women who help illustrate how ethnicity, region, culture, and race relate to Women’s Education – Women’s Empowerment.

The 2012 Honorees are:

Emma Hart Willard, Women Higher Education Pioneer

Charlotte Forten Grimke, Freed-man Bureau Educator

Annie Sullivan, Disability Education Architect

Gracia Molina Enriquez de Pick, Feminist Educational Reformer

Okolo Rashid, Community Development Activist and Historical Preservation Advocate

Brenda Flyswithhawks, American Indian Advocate and Educator

The stories of women’s achievements are integral to the fabric of our history. Learning about women’s tenacity, courage, and creativity throughout the centuries is a tremendous source of strength. Knowing women’s stories provides essential role models for everyone. And role models are genuinely needed to face the extraordinary changes and unrelenting challenges of the 21st century. National Women’s History Month, designated by Joint Resolutions of the House and Senate and Proclamations by six American Presidents, is an opportunity to learn about and honor women’s achievements today and throughout history.

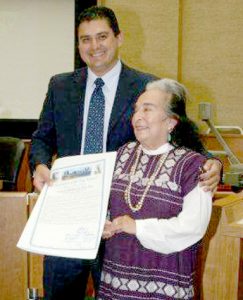

Gracia Molina de Pick of San Diego, Feminist, Educational Reformer, Community Activitist

Gracia Molina de Pick is a force of nature—an activist, feminist, educational reformer, and philanthropist who has said that one’s “individual life only has meaning if you unselfishly engage as sisters and brothers in the fight for equality, justice, and peace.” Born in Mexico City in 1930 and raised in a family that valued political activism, Molina de Pick’s community organizing skills developed in high school, where she was involved in post-World War II peace movements and political efforts to get women the right to vote in national Mexican elections. By 16, she founded and led the youth section of the Partido Popular, the only political party at the time that advocated women’s voting rights.

Molina de Pick moved to California in 1957, and earned two degrees in Education. She remembers that in her early days of teaching in a school where seventy percent of the students were Hispanic, children whose only language was Spanish, were placed in classrooms for those with developmental disabilities. She was appalled by the number of Mexican students who were in those classes, and were—in her words — “Failing miserably, miserably.” She said “No way, no way”—and thus began a crusade for change.

Realizing the critical relationship between parents—especially mothers—and their children’s education, Molina de Pick built library resources and created reading opportunities to engage the whole family. On the faculty at Mesa College, she founded and wrote the curriculum for the first Associate’s Degree in Chicana/Chicano Studies, which appeared in the Plan de Aztlan, the 1970 blueprint for Higher Education for Mexican Americans. She was the founding faculty of the Third College (now Thurgood Marshall College) at the University of California, San Diego, where she developed the undergraduate sequence for Third World Studies.

Molina de Pick is the found-er of several organizations that bring together her passionate work on behalf of women’s equality, native communities, labor and immigrants’ rights—among them IMPACT, a community organization fighting for the civil rights of Mexican Americans in San Diego; and the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional, the first national feminist Chicana Association. She also served on the National Council of La Raza, the first Civil Rights Advocate group for Mexican American Civil Rights.

The tireless Gracia Molina de Pick, now eighty three years old, whose early philanthropy was in the giving of her time, intelligence, and spirit has turned in later years to giving financial resources as well. “I don’t have a lot of money,” she says, “but I’m rich in so many other ways. Everything I have, I give to the causes.”

Arturo Castañares

Arturo Castañares